The Demon-Haunted World

One morning, you awake to find your world haunted by demons and yourself tasked with managing their influence on humanity. Acknowledging the spirits only gives them strength but turning a blind eye casts the world in darkness. You didn’t sign up for this, navigating a perilous metaphysical landscape, but here you are, once a rank-and-file practitioner of your craft now thrust into the role of spiritual guide. You can’t do this alone, and indeed your charter demands that you don’t. Rather, you must appeal to a council of elders imbued with the power, inherited by birthright, to divine the correctness of your actions and mandate a righteous path forward. Only then may you be equipped with the tools necessary to carry forth your sacred duties.

This isn’t fantasy. It’s the situation California archaeologists awoke to find on October 11th, 2023, the day after Governor Gavin Newson signed Assembly Bill 389, which prohibits the use of Native American artifacts for education or research in all 23 California State Universities. Or in the words of the law, California State University should:

Adopt and implement…a policy that prohibits the use of Native American…cultural items for the purposes of teaching or research at the California State University...

The law is the culmination of State audits and legislative actions that reclassify all precontact artifacts, what the law refers to as cultural items, to objects of sacred power. Things like chipped stone flakes and animal bones and discarded seashells, now forbidden. Moreover, AB-389 requires CSU to subject all their archaeological collections to repatriation by the end of January 2025, mandating they:

…identify and estimate….the funding and other resources it needs to complete repatriations under the act in an appropriate and timely manner.

Somehow, without legal access to artifacts, CSU archaeologists must create a detailed budget for their disposal. This is surely a slap in the face to those who have spent decades caring for these objects. Not just digging one’s own grave but also tying the noose.

AB-389 is riddled with ambiguity, but its intent is clear. Researching California’s human past is now illegal in the CSU system and CSU will soon be required to dispose of their archaeological collections. California archaeologists should find new jobs, and if future archaeologists take an interest in California’s past, they will need to rebuild the last century’s worth of knowledge from scratch.

California’s betrayal of the past has a long and complicated history worthy of a book-length treatment. Accounts of this history are ambiguous and laden with errors and inconsistencies, even within formal government audits and legislative text. It’s a mess. But here, I do my best to sort it out and tell the story of how California outlawed archaeology.

CalNAGPRA

It starts with NAGPRA, the Federal legislation that requires museums and repositories to repatriate Native American graves. After passing in 1990, many states passed their own “mini-NAGPRA’s” through their respective legislatures intended to better implement the Federal law and fill gaps in NAGPRA’s state-level reach. Of those, California’s CalNAGPRA, passed in 2001, was one of the earliest and thus served as a model for many since.

CalNAGPRA largely deferred to its Federal counterpart but expanded its reach considerably. NAGPRA only applied to institutions receiving Federal funding, so CalNAGPRA expanded its scope to include those receiving California State funding as well, like local museums. This provision has since been repeated in virtually every U.S. state. My state, Wyoming, finally passed a similar law in 2018, requiring human burials discovered on private and state lands be subject to recovery and repatriation. As it often is, California was a leader in national trends.

On September 25th, 2020, Governor Gavin Newson signed Assembly Bill 275, an amendment to CalNAGPRA that radically changed the law’s scope. The bill’s author and primary sponsor was James Ramos (D), a Serrano/Cahuilla Tribal member and the first Native Californian to be elected to the California House. On the heels of the ‘summer of racial reckoning’, AB-275 passed unanimously and was heralded in California’s media as a triumph of Indigenous rights.

AB-275 represented a fundamental shift away from the spirit and intent of NAGPRA by subjecting the entirety of California’s precontact archaeological record to repatriation and shifting the responsibility for deciding what gets repatriated and to whom solely onto the shoulders of Tribal members. As Ramos stated on NPR shortly after the law passed, Tribal elders now have the ‘last say’ in the repatriation process, with other information typically consulted in these matters, like archaeology or history, left behind.

“Cultural Items”

AB-275 is an extensive amendment with a long list of mandates, but most stem from a subtle but impactful change to the definition of cultural items. Between 2001 and 2020, CalNAGPRA deferred to NAGPRA to define cultural items. Cultural items was a catch-all to create efficiency of language in the legislative text referring to material culture subject to repatriation other than human remains, including funerary items, items of cultural patrimony, and sacred objects. AB-275 (8012.g) tacked on additional language (bolded below) that states:

“Cultural items” shall have the same meaning as defined in Section 3001 of Title 25 of the United States Code, as it read on January 1, 2020, except that it shall mean only those items that originated in California and are subject to the definition of reasonable, as defined in subdivision (l). An item is not precluded from being a cultural item solely because of its age.

There’s two things to unpack here. First, including the statement about age ensures that ALL archaeology between 13,000+ years ago and present will be subject to repatriation. Previously, archaeology older than a few thousand years was deemed difficult to affiliate with modern people, and rightfully so. Nobody in the world can accurately affiliate ancient items with modern people independent of genetic, archaeological, or historical research. This research grows more difficult as artifacts grow older, and at some point it becomes impossible. That’s why some human remains and artifacts were classified as unaffiliated with modern people after initial NAGPRA inventories were completed in the 90s. There was simply no way to tell who they belonged to. This revised definition accounts for that “loophole” in the law, though NAGPRA’s authors would tell you that unaffiliated was a feature of the law, not a bug.

Second, as with many vague laws, the word reasonable does alot of heavy lifting in AB-275. Referencing subdivision (l), we see that:

“Reasonable” means fair, proper, rational, and suitable under the circumstances. Tribal traditional knowledge can and should be used to establish reasonable conclusions with respect to determining cultural affiliation and identifying cultural items.

So reasonable means whatever your Tribal consultant says, who it is implied possesses a unique capacity for being fair, proper, rational, and suitable. Going further down the rabbit hole, we see a term first emerge that we’ll see again: Tribal traditional knowledge. Tribal traditional knowledge is:

…knowledge systems embedded and often safeguarded in the traditional culture of California Indian tribes and lineal descendants, including, but not limited to, knowledge about ancestral territories, cultural affiliation, traditional cultural properties and landscapes, culturescapes, traditional ceremonial and funerary practices, lifeways, customs and traditions, climate, material culture, and subsistence. Tribal traditional knowledge is expert opinion.

The information sources subsumed by Tribal traditional knowledge are all great things to consider when conducting repatriation and have been extensively consulted for 30 years prior to the passage of AB-275. Talking to Tribes is informative, as anthropologists have known for over 100 years.

The difference here, however, is that Tribal traditional knowledge is lent supremacy over the decision-making process as expert opinion, an honor withheld from archaeologists, anthropologists, or other subject matter experts. It is an overtly race conscious stipulation that ensures the decisions of those with racially pure Indigenous ancestry hold more weight than those without it.

I was pleased to see that the Society for California Archaeology was also confused by cultural items. But to recap the best I can, AB-275, through a series of intra-text references and vaguely-defined terms, reclassifies cultural items from a strictly-defined set of artifacts detailed in Federal law to ALL of California’s precontact material culture regardless of age. If you doubt the intent, one need only look to other stipulations in AB-275 for confirmation.

For example (8013.B.1.c.ii):

Tribal traditional knowledge shall be used to establish State cultural affiliation and identify associated funerary objects. The museum also shall record any identifications of cultural items that are made by tribal representatives. The identifications may include broad categorical identifications, including, but not limited to, the identification of everything from a burial site as a funerary object.

Or, in describing how to compile a preliminary report of cultural items due on January 1st, 2022:

The agency or museum…shall record any identifications of cultural items that are made by tribal representatives. The identifications may include broad categorical identifications, including, but not limited to…the identification of everything from a specific site as a sacred object because that site is a sacred site.

AB-275 was a harsh reality for California archaeologists. ALL California archaeology is now subject to repatriation, from those objects for which NAGPRA was originally intended, like burials, to discarded stone tools and animal bones. This reality was acknowledged by the Society for American Archaeology in an email sent to its California membership on June 22nd, 2020, but it was quickly rescinded by then President Joe Watkins on June 24th after an outcry from activitists within the Society’s ranks.

Maybe SAA’s statement was too hastily released, as Watkins put it. Maybe AB-275 was a positive step forward for California’s Tribes, who would accurately identify items with sacred significance in good faith and leave the rest for archaeologists to continue their work. As evident from actions taken since, that good faith is in short supply.

Audit Theatre

With the passing of AB-275, the legislative infrastructure was in place to repatriate much of California’s archaeological record. But disposing of that much scientific data, data that had taken over a century and at least hundreds of millions of dollars to amass, remained a hard sell. So Ramos and his allies in government set out to undermine CSU’s reputation by subjecting them to an audit they were sure to fail.

Some media accounts attribute CSU’s audit to a single individual: Elizabeth Weiss. Weiss had made a name for herself as an outspoken critic of NAGPRA, and as a faculty member at San Jose State University in California, she was a notable outlier in the state’s political landscape. Weiss posted an image on Twitter posing with a Native American cranium housed in San Jose’s collection, captioning it “So happy to be back with some old friends,” which illicited strong rebuke from repatriation activists.

While I’m certain Weiss’s post didn’t HELP CSU’s cause, I’m also skeptical that it inspired the audit of 23 CSU institutions. Surely one Tweet from one professor at one school wasn’t enough to justify the enormous expenditures of time and money spent auditing CSU’s anthropology departments. Rather, I suspect the proponents of the audit needed a scapegoat to justify their actions, and Weiss served that role well.

State auditor Grant Parks began his audit in 2022, soliciting surveys from all 23 institutions and visiting four in person to assess CalNAGPRA compliance. Taken at face value, the key conclusions of the audit were shocking:

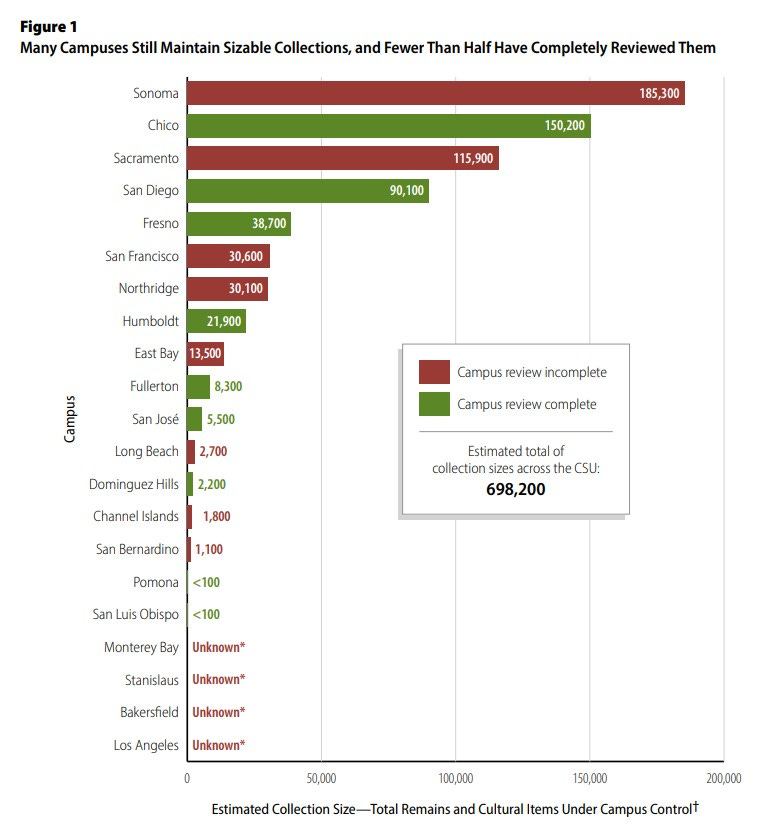

of the 21 campuses with NAGPRA collections, more than half have not repatriated any remains or cultural items to tribes…More than half of these 21 campuses do not yet know the extent of their collections of remains and cultural items, despite federal law requiring them to do so by late 1995….Factors such as these have contributed to the CSU system making little progress in the timely return of human remains and cultural items to tribes, repatriating just 6 percent of its collections to tribes to date.

Shocking? Yes. But only because the audit conclusions are a shockingly brazen political fabrication written under AT LEAST unrealistic if not entirely false pretenses. For example, the statement that CSU had failed to inventory their NAGPRA collections “despite Federal law requiring them to do so by 1995” is entirely false. The inventory requirements as now defined by AB-275 didn’t exist in 1995. And the rebuke that CSU has repatriated “just 6 percent of its collections to tribes to date” is completely unrealistic. The requirement to repatriate all collections was only (vaguely) stipulated by AB-275 when it went into effect in 2021. Given that the process for repatriating even 1 individual often takes several years to complete, from research, to consultation, to listing, to return, a two year window to repatriate the 700,000 total objects reportly housed at CSU institutions seems impossible.

The audit’s issues are extensive and I won’t detail them all here. I don’t know if State Auditor Grant Parks was ignorant of the legislative history that led to this audit or if he willfully manipulated it to malign CSU’s reputation. Either way, it’s an abuse of his position and, in my opinion, the ambiguous terms, misleading statements, and false accusations reported in the 2023 audit are severe enough to warrant retraction.

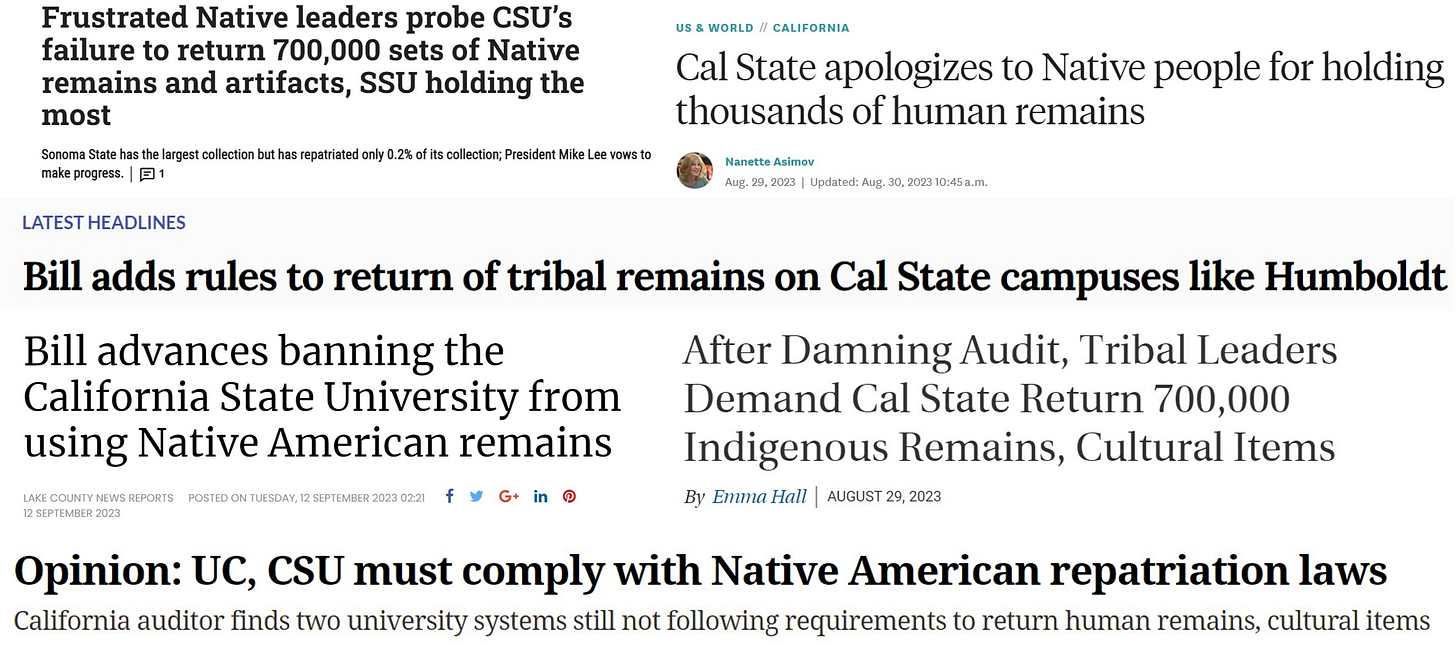

But that hardly matters now. The media was eager to jump on the story to create a tidy narrative about a legacy institution abusing marginalized cultures. The headlines wrote themselves.

The issue snowballed into an avalanche whose momentum was too great to stop. Ramos passed AB-389 unanimously through every body of government in which the bill was subject to a vote. The House, the Senate, and several committees. Not a single California representative opposed AB-389 and now precontact archaeology is illegal at CSU.

No End in Sight

By any objective measure, Ramos won. He shamed CSU in the eyes of California’s public and built an unprecedented degree of political consensus to pass a law banning California archaeology from the CSU system. You’d think he’d step back, smoke a cigar, and take a break for a job well done. But it appears as though he’s only getting started.

Concurrent with AB-389, Ramos was instrumental in passing AB-226, a similar but shorter law catered to the University of California system. For reasons I don’t know, the UC system is only “strongly urged to prohibit use of any Native American human remains or cultural items for purposes of teaching or research” rather than outright prohibition. AB-226 also requires TWO further audits of the UC system in addition to one conducted in 2020 (not discussed here for time), so I suspect it will have an equally chilling effect on archaeological research and ultimately lead to its outright prohibition.

At a larger scale, much of the legalese adopted by California during the last several years appears to be making its way to Washington. 2022’s proposed revisions to the Code of Federal Regulations (CFRs) that implement NAGPRA include similar language as 2020’s CalNAGPRA (AB-275) amendment. In the most glaring example, revised NAGPRA CFRs add traditional knowledge to the list of information sources used to establish cultural affiliation and identify items for repatriation. Language in both documents lists traditional knowledge as “solely sufficient” for doing so. NAGPRA’s proposed definition for the term is oddly similar to that in CalNAGPRA, to the point where portions seem cut and pasted:

Native American traditional knowledge means knowledge, philosophies, beliefs, traditions, skills, and practices that are developed, embedded, and often safeguarded by Native Americans. Native American traditional knowledge contextualizes relationships between and among people, the places they inhabit, and the broader world around them, covering a wide variety of information, including, but not limited to, cultural, ecological, religious, scientific, societal, spiritual, and technical knowledge. Native American traditional knowledge may be, but is not required to be, developed, sustained, and passed through time, often forming part of a cultural or spiritual identity.

Obviously, a core group of repatration activitists is behind many of the sweeping changes to heritage management legislation currently underway in the United States, exporting precedents set in California to the Nation at large. Who they are, I don’t know. The Feds make it difficult to determine the names of the unelected officials that write and then self-approve many of their laws. But if California is to serve as a bellwether for cultural trends, as it often does, I am concerned for the future of North American archaeology as a whole.

Why I Disagree

If it’s not apparent, I think banning archaeology is bad, but it’s worth explaining why. First, and very simply, I think archaeology is valuable. To say so doesn’t imply that archaeology is blameless or ethically spotless. Like anything, archaeology has committed its share of missteps, “past harms” for which archaeologists have actively apologized. To say archaeology is valuable only implies that it’s a net positive for the world, having done more good than harm. I think its contributions to understanding the human past are enough to justify this claim in its own right, but as “the most scientific of the humanities,” this value goes well beyond rote empiricism. As a local example, religious and racist dogma questioned American Indian claims to cultural patrimony in the early history of the United States, and archaeology provided much of the evidence needed to convince the American public otherwise. One need not search long to find American Indians pointing toward archaeology to justify cultural patrimony even today. We’re a long ways from 19th century notions of Native North America, and we largely have archaeology to thank for that.

Archaeology’s humanistic contributions were made possible by the liberal democracy of the United States, in which free speech and open inquiry enabled archaeology to flourish. I view California’s new laws as a direct attack on those values. AB-389 prohibits a scientific discipline and mandates the destruction or obfuscation of all physical evidence that it existed. We have terms for that sort of policy, and liberal is not one of them. Given AB-389’s racial and religious basis, ethnonationalist and theocratic come to mind. Perhaps some would like to see the United States move further in that direction, each identity group entitled to their own set of laws that neatly partition the Nation into a jigsaw puzzle of tiny, divided pieces. I don’t.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that AB-389 doesn’t just rob archaeologists of the right to study the past. It robs Native Californians of that right as well. I see no evidence that AB-389 was drafted by a diverse coalition of California Indian Tribes and heritage professionals. The law and those related to it were all drafted and ushered through California State government by a single man representing one Tribe among California’s ~200. Many of those Tribes have long-standing and productive relationships with archaeologists, with whom they have collaborated in creating a rich, mutually-beneficial body of research. That work is now over. Viewed in this light, these laws are less a triumph of Indigenous rights than they are of one man, who imposed his will on everyone else through the heavy hand of government.

As California Goes

I’d like to wrap this up with a confession: I love California. When I blindly accepted a job in Susanville, California in 2009, I did so as a proud southern Appalachian that had never traveled west of Denver, sure in my conviction that whatever I’d been told about the Golden state, it surely ain’t all it's cracked up to be. I was wrong. Susanville was NOT the California romanticized for popular consumption. No palm trees, but endless expanses of sagebrush and juniper. No sandy beaches, but high desert peaks that hold snow until July. A wild, barely tamed corner of the Lower 48 that never makes the big screen, but that satisfied the rambling urges of a man in his early 20s. It turned out that California was everything it claims to be and much more, one of the most beautiful places on earth still buzzing with the aura of possibility.

But my most enduring impression of California, the one it keeps reaffirming to me, is that it is fundamentally insane, defined by extremity rather than temperance. Its very shape belies its manic character, holding within its borders both the lowest and highest elevations in the lower 48 United States, only 88 miles apart. And its politics, typically caricatured as bleeding heart liberal, span the entire range of American political philosophy, from overt white supremacy to Marxism and everything in between. Susanville remains the most conservative place I’ve ever lived, just a few hours east of America’s leftist beating heart in the Bay Area. You can be anything you want in California, as long as it’s not boring.

California’s propensity for extremity permeates every aspect of its character, extending even to the ways it legislates. That tendency to create grand legislative gestures often falls flat. But sometimes it results in revolutionary, positive changes to the lives of Californians, and by extension those of other states who follow their lead. Medical marijuana legalization, prison reform, and early civil rights legislation come to mind.

I think the bills advanced by Ramos were intended to join the ranks of California’s grand progressive gestures, but they missed the mark completely. Actions intended to “start the healing process” are merely a shot in the arm, dulling the pain of historical injustices for a moment while allowing the wounds to continue festering. These bills will lead to the continued destruction of California’s vulnerable heritage resources, resources valued by Euro and Native Californians alike for the depth of understanding they contribute to modern life. So when the smoke clears and we return to write the history of this era, I think historians will view these laws not as grand achievements, but as misguided and needlessly destructive political gestures. That is, unless those historians are too occupied rewriting California’s past from scratch.

While I understand that science can be harmful and that appropriate restrictions should be put in place to prevent harm, this law is far from appropriate. A few examples of the kinds of censorship that result from this law demonstrate the absurdity of using archaeology as a politically expedient target accomplishing for social justice goals.

ILLEGAL: A CSU professor studying what people ate in the past.

ILLEGAL: A CSU student measuring flakes from a surface scatter of chipped stone

ILLEGAL: A CSU professor studying how past peoples stewarded California's natural resources

ILLEGAL: A federally recognized tribe in California hiring a CSU professor to do archeological research

ILLEGAL: An indigenous student working on a graduate degree at a CSU studying their own past through material remains

ILLEGAL: A CSU researcher using data from archaeological sites to establish ecological baselines for modern marine ecosystems.

It really bums me out to see the political party that claims to care about science ban the scientific study of the human past with zero debate.

You may be interested in a couple of my links on these issues. The first is my Op-Ed on AB275, which caused much more hysteria than my tweet. Had I been a repatriation-loving archaeologist, no one would have had any issue with my tweet (as evidenced by the many similar photos by archaeologists)

https://www.mercurynews.com/2021/08/31/8314049-native-american-remains-uc-ab275-graves/

and, my most recent op-ed

https://californiaglobe.com/fr/california-buries-science/

And, for a longer read on the issue of teaching collections, my article in Skeptic with James W. Springer:

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A766112775/EAIM?u=nysl_oweb&sid=sitemap&xid=e6c9eed5