Holy Ground

Certain places are Holy ground for those who study the past. Places where the past manifests itself so clearly in the present that visiting them transports us to another time. For Mississippian archaeologists, St. Louis’s Cahokia Mounds site might be that place. For Southwestern archaeologists, Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonita. Places where past people constructed massive monuments to their societies that remain visible today, making their imprint on North American history hard to ignore.

Paleoindian archaeologists working in the middle of North America have no such monuments at which to pay homage to the past. Paleoindians didn’t build giant mounds or enigmatic, crescent-shaped apartment complexes in the desert like the horticulturalists of later times. For the most part, they left scatters of stones and bones in campsites and, occassionally, large piles of bison bone lying where they were killed thousands of years ago. But if there is Holy ground for North American Paleoindian archaeologists, it might be the Hell Gap site.

For those that study Paleoindian archaeology, the Hell Gap site is known quantity. For others, I’ll briefly summarize. Hell Gap was discovered by a couple of Wyoming locals in the 1950s and excavated by Harvard over several years in the 1960s. They ended up discovering a large complex of intact, buried archaeological sites situated at the margins of a mile-long reach of an ephemeral drainage at the eastern margin of the Hartville Uplift. The valley contains archaeology of all ages, but the most intact and extensively researched is buried within several Paleoindian-aged Localities, labeled I-V.

Hell Gap’s crown jewel is Locality I, which contains a continuous sequence of campsite occupations by at least eight Paleoindian cultures spanning ca. 12,800 to 8,500 years before present. At Locality I, Harvard’s Irwin siblings revealed thousands of artifacts buried within a 2-meter deep stratified sequence indicative of people camping in the same location for several thousand years. In the process, they named THREE new Paleoindian cultures and assigned them ages using radiocarbon dating for the first time. Here, archaeologists could see not only snapshots of the deep past, but a veritable movie, changing shape and character through time as Wyoming’s earliest people adapated to the ever-changing environment of the post-Pleistocene Plains. It was, and remains, the most comprehensive record of Paleoindian archaeology ever discovered in the North American mid-continent.

Historic Property

The Hell Gap site is on private property. So after the Irwin’s completed their work at the site in the mid-1960s, the property returned to its previous use as a cattle ranch for a couple decades. But the Wyoming archaeological community never forgot about the phenomenal array of artifacts excavated by Harvard, so they banded together to purchase the property in the early 1990s. Since then, Hell Gap has been the private property of archaeologists, managed by the Wyoming Archaeological Foundation for archaeology, historic preservation, cattle grazing, and hunting.

The Hell Gap site property subsumes about 350 acres of dry rangeland covered in sagebrush, pine, and juniper. West of the property, the rocky canyons of the Hartville Uplift mark the easternmost foothills of the Rocky Mountains. East of the site, the High Plains of eastern Wyoming stretch as far as the eye can see, interrupted by signs of modernity only at night by the distant airport lights of Scottsbluff, Nebraska. During the summer months, massive thunderstorms crack and flash daily in the distance, moving slowly across the open plains of eastern Wyoming. Those who have spent time there will tell you that the punishing storms, by some fluke of geography or weather or perhaps something spookier, almost always miss Hell Gap. Perhaps yet another reason why people found the valley so appealing for so long.

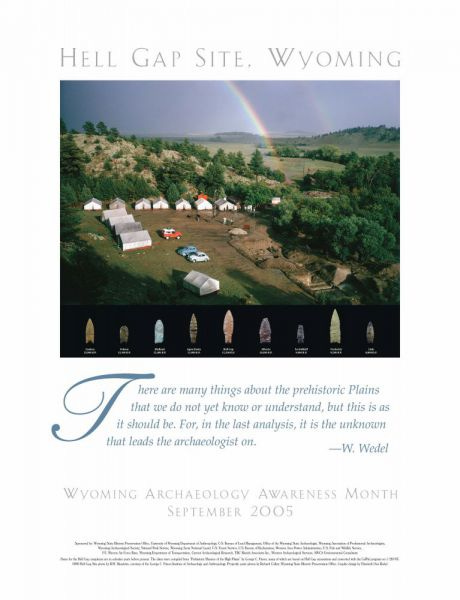

Hell Gap is still used for cattle grazing, but for 6 weeks each summer archaeologists converge on the site to chip away at excavations at Locality I that have been ongoing since the late 1990s. Marcel Kornfeld and Mary Lou Larson have supervised excavations at the site for around 25 years, hosting a field school there each summer that has produced an impressive number of Plains archaeologists that have gone on to lucrative careers. Most people I know have done some time at Hell Gap, carefully peeling away Pleistocene sediments, painstakingly plotting flakes and bones, and, importantly, learning how to live in a Wyoming field camp. It’s a veritable rite of passage at this point.

But alas, all things must pass, including long careers in Wyoming archaeology. Marcel Kornfeld is retiring soon, and with him a long tradition of summer fieldwork at Hell Gap. It’s bittersweet for those who have come to love their annual pilgrimage to the site, but it’s also a logistical problem. Decades of work at the site have accumulated an impressive compound that includes a house, several trailers, buildings, a tractor, and an array of miscellany used to facilitate excavations at the site. With nobody around to care for them, they will surely fall rapidly into disrepair. Seeing this, we decided to step in for a bit until Hell Gap becomes an annual destination for archaeologists once more.

Living in Hell Gap

I spent a week this summer living at Hell Gap with the 2023 field school. I’d visited Hell Gap plenty, excavated there some, and generally look forward to my time there each year, hot as it may be in the dolrums of July. But I’d never really stayed there for longer than a couple days, so this year I wanted to get the full experience.

I helped cook and clean, learned the nuanced details of how excavations are conducted, inventoried and photo’d the buildings and trailers, had long conversations with Marcel and other long-time site workers, and in the evenings ambled around the 350 acre property feeling grateful for those with the vision to purchase the property when I was still in grade school.

I also spent some time working, placing a mapping datum in a new area of the site never before investigated by archaeologists. Locality IV is the southern-most locality at Hell Gap, having been known since the earliest investigations as a parking area and Holocene-aged terrace of minimal interest to the Paleoindian archaeologists who typically work at the site. But in 2018, a fluted Folsom preform was discovered at Locality IV, eroding from sediments thought to be several thousand years too young to contain an artifact dating to the Late Pleistocene. So I thought a good first step in perpetuating work at the site would be setting a new excavation block over this never before investigated portion.

Of course, you can’t kick a rock at Hell Gap without turning up an artifact, so we excavated the concrete mapping datum hole systematically in a 50x50 cm unit down to about 40 cm below surface, deep enough to support a big concrete plug into which we placed an aluminum datum cap. That modest effort yielded over 3,000 artifacts, which gave us a good idea of what we might be into should someone begin excavating at Locality IV.

The Future of Hell Gap

So we’ve got this big property owned by archaeologists. It’s filled with a dense accumulation of very rare archaeology, but also a ton of infrastructure in need of routine maintenence. There’s no shortage of archaeologists willing to stick their trowels in the ground at Hell Gap, but there are far fewer with the dedication to take on facilities maintenence or processing tens of thousands of artifacts each year. It’s a commitment that requires weeks of one’s time annually and no small amount of funding.

That being said, I left Hell Gap this year with the impression that yes, archaeologists should continue working at the site, and we should do whatever it takes to make that happen. Hell Gap is not just a world-class archaeological site, it’s become a cultural destination for Paleoindian archaeologists across the country, and really world, who visit the site each year to view what new discoveries have emerged, flint knap, socialize, hike, and make new friends. In many ways, Hell Gap is once again fulfilling the role it may have during the Pleistocene, as a place to gather, exchange, and live among one’s distant relations, and that’s something well worth preserving.

This newsletter is as much Field Notes as it is a call for the many archaeologists that follow this from around the country to consider putting some time into Hell Gap. Come help excavate for a week to check it out, then maybe host a field school session there, or later even consider developing a long-term research project. Archaeologists own this site so that archaeology can be done there, so please reach out if you’re interested.

Very informative! Thanks