Mummy Cave: A Wyoming Treasure

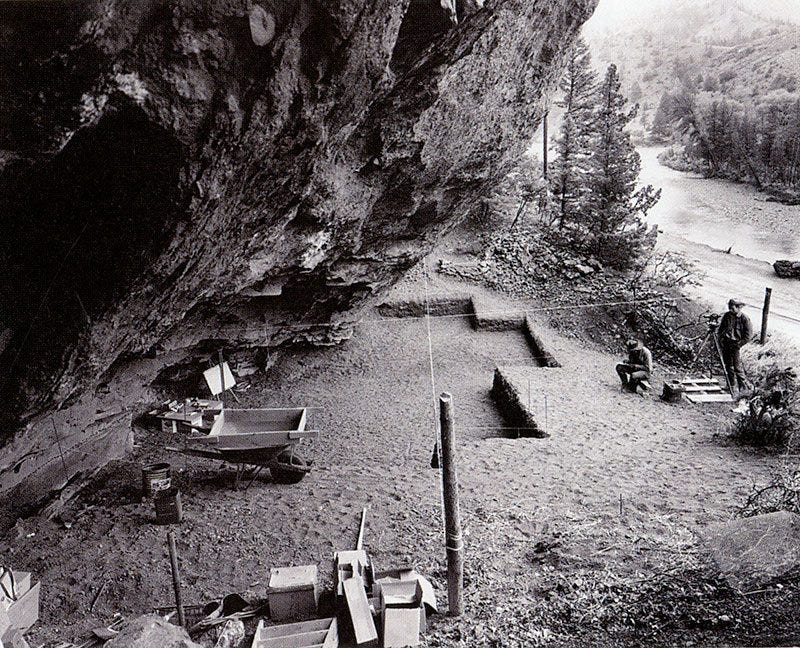

In a state known for its remarkable archaeological sites, Mummy Cave is one of Wyoming’s crown jewels. The stately, overhanging cliff is perched above the North Fork of the Shoshone River, a shallow alcove having been carved from its base by an ancient meander of the river where for 10,000 years Wyoming’s Native residents sought refuge from the elements. Today, the site is located only meters from the busy North Fork Highway, where millions of tourists each year pass on their way to the east entrance of Yellowstone National Park. If you find yourself in the area, Mummy Cave is worth a stop. The roar of the North Fork echoes off the back wall of the shelter, drowning out the noise of passing cars and providing a serene accompaniment to your visit, little changed for the last 10,000 years.

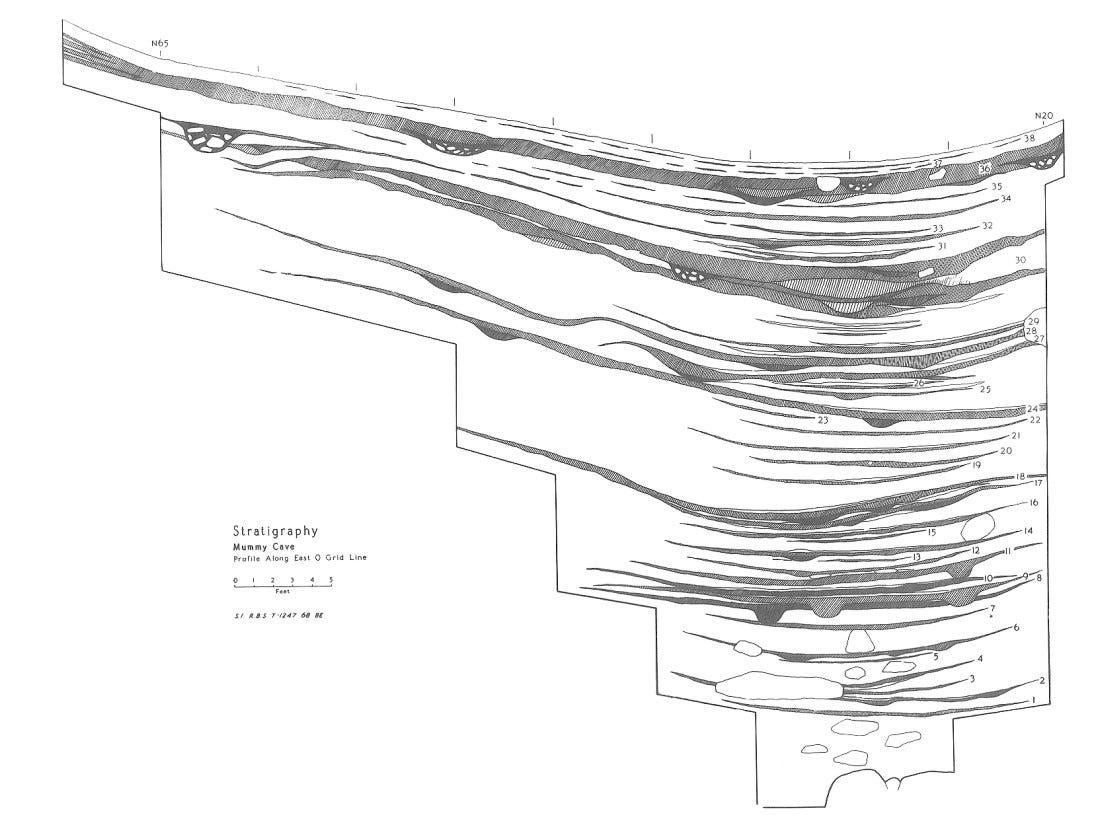

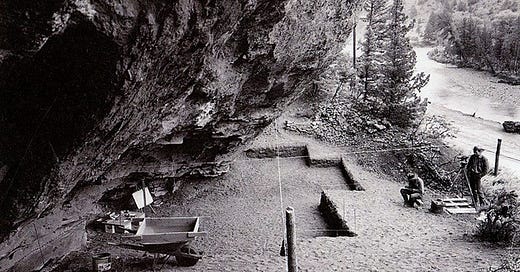

An aesthetic beauty in its own right, Mummy Cave’s larger significance lies in the thick deposit of sediment accumulated in its floor. Sediments have gradually washed into Mummy Cave from either side of the rock overhang since the end of the last ice age, neatly preserving human occupations at the site throughout this time. Excavations between 1963 and 1966 supervised by local avocational archaeologist Bob Edgar and Smithsonian archaeologist William Husted uncovered evidence for at least 38 cultural levels buried throughout 10 meters of sediments spanning 10,000 years ago until just prior to European contact. The stratified human occupations were the most extensive ever discovered in the Rocky Mountains at that time, and they remain so today. Indeed, Mummy Cave is one of the most temporally extensive and high fidelity archaeological records in the entirety of the American West, rivaling better known sites like Gatecliff Shelter and Danger Cave in its ability to inform archaeologists about past hunter-gatherer lifeways and how they changed through time. And, as you may have guessed, there was a mummy.

Mummy Joe

Mummy Cave’s namesake is a naturally desiccated human burial found near the back of the rock overhang. The individual is a 35-40 year old Native American man, wrapped in an ocher-stained sheepskin blanket and with rabbitskin earmuffs placed over his head. A semi-circular cobble stone wall was placed around and on top of the man to partition him from the rest of the shelter’s living space. He was likely interred early in the occupation of cultural level 36 (CL36), a cultural level that includes many occupations spanning perhaps several hundred years between AD 500 and 1200, though the level itself has never been radiocarbon dated. The sheepskin blanket wrapped around the man was dated to 1230 +/- 110 radiocarbon years before present, or around AD 800.

Mummy Joe, as the man came to be known, was placed on display shortly after his discovery in the Whitney Gallery of Western Art in Cody, WY, where he remained for several years. National news of the discovery in 1963 was a crucial selling point for Harold McCracken, the Director of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center responsible for funding the excavations. After reaching far-flung news outlets such as the Chicago Sun Times, several private donors and the National Geographic Society offered to fund continuing excavations at Mummy Cave. Surely, excited donors expected McCracken to continue unearthing additional ‘mummies’ from the site, but no additional human remains were found.

Placing Mummy Joe on public display was in poor taste, to put it mildly. But such practices were common at the time, and to the Museum’s credit, they removed Mummy Joe from display before Federal legislation made it mandatory (or at least strongly encouraged) for them to do so, transferring him into long term storage at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West (BBCW).

Mummy Cave is on land administered by the U.S. Forest Service, so Mummy Joe was subject to repatriation under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) upon its passage in 1990. Although the BBCW submitted an notice to facilitate the repatriation of Mummy Joe in 1995, the notice was not published in the Federal Register until 2006 due to the enormous backlog accrued by the Department of the Interior in the early days of NAGPRA implementation. The inventory lists the sheepskin blanket wrapped around Mummy Joe as the sole associated funerary object and recommends repatriation to the Eastern Shoshone of the Wind River Reservation, WY and the Shoshone-Bannock of the Fort Hall Reservation, ID, an affiliation based largely on analysis presented by Husted and Edgar (2003). For unknown reasons, Mummy Joe was not claimed by either Tribe after inventory publication, though the BBCW reached out to both Tribes directly to notify them. Mummy Joe continues to reside in the BBCW, but a recent updated inventory published in the Federal Register on July 1st, 2022 may soon result in his repatriation, along with much of the largely undocumented archaeological assemblage from cultural level 36.

Repatriating refuse

I know few archaeologists that object to responsible repatriation under NAGPRA, and all I have spoken to about this case in particular agree that Mummy Joe’s repatriation is long overdue. But the 2022 NAGPRA inventory “correction” goes far beyond the repatriation of an individual and the funerary objects with which he was buried. Tucked into the 3rd paragraph of the supplementary information is a correction to the number of funerary objects associated with Mummy Joe to include “all items removed from cultural level 3/36.”

Cultural level 36 (CL36) is only one level of Mummy Cave, but it comprises a large percentage of the total artifacts recovered from the site because it was extensively excavated and especially dense with artifacts. In addition to the typical stone and bone artifacts common to most hunter-gatherer campsites, Level 36 contains many perishable items rarely discovered by archaeologists, some of which unique to the site in Wyoming. These include hafted arrows and arrow parts, bows and bow parts, human coprolites, moccasins, animal snares, hide, a bone harpoon (unique to the site), bone pendants and beads, brush and sinew cordage, knife handles, a fire drill, basketry, and several dozen other types of perishable objects. It is among the largest assemblages of perishable artifacts ever discovered in the Rocky Mountains, a result of the excellent preservation conditions present beneath the rock overhang at Mummy Cave.

Upon examination, it is clear that the “inventory correction” published by the U.S. Forest Service is actually the reclassification of an entire assemblage of campsite refuse as funerary objects in order to facilitate its repatriation via NAGPRA. If it goes through, destruction or removal of inclusive access to the CL36 assemblage via repatriation would be among the largest losses that the Rocky Mountain archaeological community has ever faced, and it is unlikely that another CL36 will ever be discovered. Just as all archaeologists I know in Wyoming are enthusiastically supportive of Mummy Joe’s repatriation, all are united in their opposition to this action.

Correcting the Correction

I and those with whom I have worked on this issue am opposed to this action for several reasons, which I’ll summarize here. If interested, we have written several letters to the U.S. Forest Service objecting to this action that I am glad to share elsewhere.

First, the concept of association is a key component of NAGPRA implementation, “associated funerary objects” having been clearly defined in the 1990 law and unchanged today. NAGPRA defines them as objects that, as a part of the death rite or ceremony of a culture, are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later... The campsite refuse from CL36 in no way meets these criteria.

For starters, archaeologists could not have asked for a more obvious burial context through which to discern associated funerary objects. The burial was clearly defined by a stone partition, which segregated it from living areas of the site. That’s why the original inventory listed only a sheepskin blanket as associated. Consequently, to consider the entirety of CL36 “associated funerary objects,” one must assume that people meticulously reproduced a hunter-gatherer campsite like a 1:1 diorama around this individual’s grave as part of their burial rites. That seems unlikely.

Further, CL36 is likely comprised of several hundred years of cultural occupations spanning many human generations, though when researchers asked to radiocarbon date CL36 in 2019 the Forest Service asked them to delay analysis until NAGPRA consultation was complete . The burial is likely associated with one of these occupations, but it may have also been excavated through CL36 after its deposition. Thus, campsite refuse deposited perhaps hundreds of years AFTER or BEFORE the burial occurred (or both) are currently considered associated funerary objects. So not only are we being asked to accept that people recreated a hunter-gatherer campsite as part of this individual’s death rites, we are being asked to accept that they either pre-emptively did it decades or generations prior to their death, or came back to recreate the scenario generations later. Either scenario seems far-fetched.

Beyond association, we must acknowledge that refuse is in no human cultures of which I am aware commonly considered funerary objects. Animal bones, broken tools, random pieces of wood, blown out shoes….although remarkable to find preserved in an archaeological context, these are ultimately the sort of mundane items that accumulate in one’s house, not the sort that get placed in your grave. In the most glaring example, there are pieces of literal human feces slated to be repatriated alongside Mummy Joe. Surely the people that gave Mummy Joe a proper burial 1200 years ago would have objected to such a profane act.

And finally, I strongly suspect that Mummy Joe and the contents of CL36 are being repatriated to his extremely distant cousins rather than his lineal descendants. I am not certain how the Eastern Shoshone (ES) and Shoshone-Bannock (S-B) were chosen as recipients, but I suspect it was a combination of outdated research and modern geographic proximity. Husted and Edgar (2003:114) hypothesize that “Shoshoneans have occupied northwest Wyoming for 5 millennia,” but these conclusions were written in 1966 before finally being published in 2003. Between these published conclusions and their geographic proximity today (a criteria for affiliation based on a 2010 NAGPRA rules change), the ES and S-B probably seemed like the natural choice for repatriation by Forest Service employees anxious to get along with this process.

However, in the intervening 60 years since Husted’s conclusions, archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists, and others have made great advances in Rocky Mountains ethnohistory, and that history doesn’t place the Shoshone in the region until well after the deposition of CL36. Indeed, we now recognize the uppermost level at Mummy Cave (CL38) as a clear Shoshoean occupation, a level dating to almost 1,000 years younger than CL36 (340 +/- 90 BP). This research is not obscure; it was simply not considered. Had the Forest Service established affiliation through a combination of relevant information sources (as NAGPRA regulations specify), they would have likely concluded that the Kiowa, who now reside on a reservation in Oklahoma, are the most likely living descendants of Mummy Joe. Presenting the details of this conclusion are beyond the present scope, but suffice it to say that removing access to the CL36 artifact assemblage goes a long way toward erasing evidence for the Kiowa’s ancestral roots in Wyoming entirely.

This action fails to meet basic criteria for establishing association between human remains and funerary objects, profanely associates refuse with a human burial, and is derelict in its duty to establish cultural affiliation accurately. It is not only a bad decision, but likely illegal given requirements to preserve and care for collections from Federal lands stipulated in the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA, Section 110) and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). So how did we get here?

Freedom of information

Shortly after publication of the corrected inventory, a colleague submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for information related to the matter. The request totals almost 2500 pages of correspondence, documents, spreadsheets, and archival materials related to the Mummy Cave repatriation, some of which dating back to 1995. Its contents detail the series of actions that culminated in this decision, demonstrating how a small number of motivated individuals operating within an ideological bubble can fundamentally alter the trajectory of a well-intentioned action. Throughout this, I refer pseudonymously to individuals to maintain anonymity.

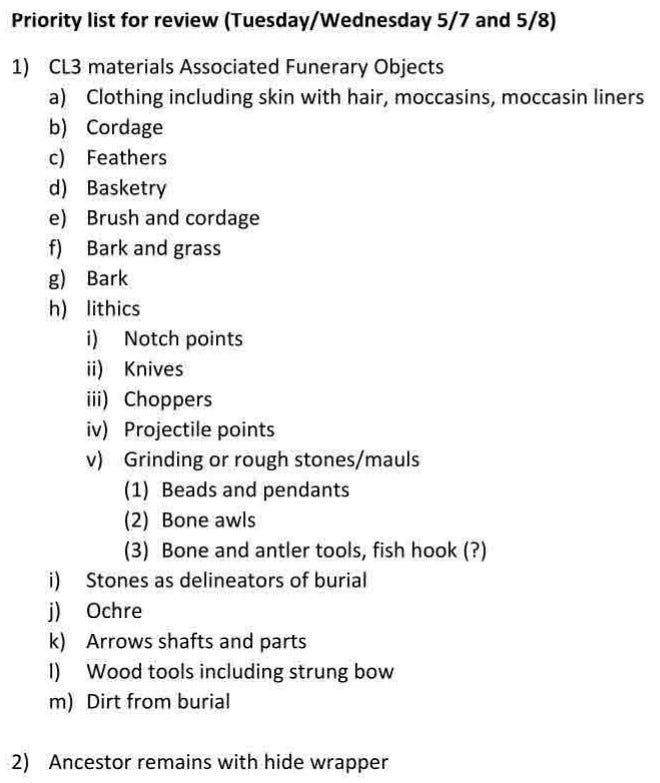

In April 2018, the Forest Service’s Regional NAGPRA coordinator (SJ) put a sole source contract in place for JB, who operates a private NAGPRA consulting firm that contracts with government agencies, Tribal entities, museums, Universities, and other institutions tasked with NAGPRA compliance. JB is an art historian and museum studies major with several decades of experience with repatriation, but as far as I can tell, none in anthropology. In May 2019, JB traveled to Cody, WY to assist the Eastern Shoshone (ES) in identifying associated funerary objects (ASO’s) from Mummy Cave’s CL36 at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West (BBCW). Prior to JB’s visit, the sole ASO is a sheepskin blanket. After the visit, the list of ASO’s had expanded to include much of the CL36 assemblage. The BBCW supplied a brief summary of the items identified as ASO’s to Forest Service representatives (see below) and this list was expanded further after another museum visit in October, 2019. The ES sent a final inventory of around 400 ASO’s to the Forest Service on March 17th, 2020.

The ES cultural committee approved the identified ASO’s in March 2021 and JB reached out to the Shoshone-Bannock (S-B) to build consensus on identified ASO’s shortly thereafter. Toward that end, JB sent an email to representatives of both Tribes containing two object lists, one reflecting the 400 objects identified as ASO’s by the ES and a second containing all other items from CL36 NOT identified as ASO’s. In the email, JB looks “forward to knowing if you consider any or all of the items in the second list also to be associated funerary objects.” Here, JB provides in writing the first indication of the intent to repatriate the entirety of CL36.

The corrected inventory took shape soon after this email correspondence. The S-B responded on August 3rd that the entirety of CL36 should be repatriated, and by August 4th, 2021 JB had sent a draft inventory correction to the Forest Service for publication in the Federal Register. Perhaps JB is a speedy draftsman, but the timing strongly suggests that the notice was already written and thus pre-ordained by JB.

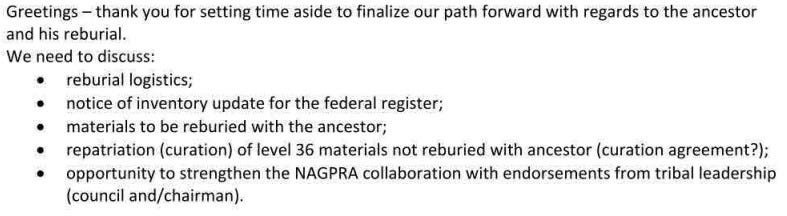

It seems several people were aware the corrected inventory might extend NAGPRA past its legal authority and thus raise unwanted attention. For instance, in a September 2nd, 2021 meeting scheduled between Forest Service and Tribal representatives, Regional NAGPRA coordinator SJ presents an informal agenda in which “curation of level 36 materials not reburied (curation agreement?)” is to be discussed. Subsequent correspondence notes that some portion of the assemblage will be considered funerary objects to be reburied with Mummy Joe and other objects will be placed in an undetermined location. Which begs the question: If CL36 is being repatriated as associated funerary objects, then why are all objects not being reburied with the individual with whom they were supposedly associated? In these conversations, we see why. These objects, though categorized in the corrected inventory as ASO’s, were never actually considered funerary objects by the people making these decisions. They were only called that for the sake of subjecting them to repatriation via NAGPRA.

Other lines of evidence suggest that JB made some effort to obfuscate their intentions in order deflect attention from those who might recognize and protest their actions. For instance, JB states on August 4th, 2021 that they “think we found a way to describe the ancestor and his belongings that will be low profile…” And in an attempt to downplay the number of objects and allow for additional items to be added to the inventory later, JB suggests grouping the items in “lots” according to artifact type rather than listing them in a comprehensive inventory. So the corrected notice lists 44 “lots” instead of the 500 or 600 objects actually being repatriated. We do not know the exact number and the Forest Service does not either.

It’s not entirely clear who’s responsible for the series of decisions leading to the corrected inventory, but one person consistently emerges in correspondence as someone willing to push the legal authority of NAGPRA: the consultant JB, a government contractor with no background in archaeology, anthropology, or any other field of study that might lend itself well to establishing the association between a buried individual and their funerary objects. First, JB was there during the initial reclassification of campsite refuse into 400 AFO’s. Later, JB orchestrated including the remainder of CL36 with the corrected inventory by compiling a list of non-AFO’s and suggesting to the ES and S-B that maybe they should be included too. And then when approval finally came through, JB had a corrected inventory notice that included the entirety of CL36 ready to go, as I suspect they always intended.

To be clear, Tribal and Forest Service representatives never questioned JB’s actions, at least not through the official channels documented in the FOIA request, and the Federal government is ultimately responsible for the final decisions made in this process. After all, the Forest Service hired JB in the first place and the cultural committees of both consulting Tribes approved each action. However, it seems unlikely that the Forest Service would have taken such an extreme stance on this case had they not been influenced by an experienced consultant with a prestigious-sounding ‘& Associates’ behind their name to guide the process.

The future of Mummy Cave

As far as I know, Mummy Joe and the CL36 assemblage is still sitting in the BBCW waiting to be claimed for repatriation. In the end, I don’t think there’s obvious or malicious wrong-doers in this affair. The Tribes want their ancestor back in the ground, and they’ll do what’s necessary to make that happen. The Forest Service has developed hard-won rapport with those Tribes after long-standing (and understandable) acrimony between Native and Federal governments. They’d be foolish to threaten that rapport by taking contrarian stances on this case. And even JB, who made what I consider to be unethical and illegal decisions, is surely motivated by a sincere desire to see Native Americans achieve greater autonomy over their past. But all the good intentions in the world can still be corrupted, as this case shows.

The loss of inclusive access to the CL36 collections, whether by reburial or through transfer to a non-accessible facility, is a huge loss to science, and I won’t pretend like that’s not my primary concern. Archaeologists devote their careers to understanding how humans lived their lives in the past, and assemblages like CL36 are enormously important to that endeavor.

But beyond my personal feelings, protection of these resources and the facilitation of their research is mandated by Federal law. For instance, Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) states that:

records and other data, including data produced by historical research and archeological surveys and excavations, are permanently maintained in appropriate databases and made available to potential users pursuant to such regulations as the Secretary shall promulgate.

Likewise, codes of Federal regulation that implement the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) (36 CFR 79) state that:

The Federal Agency Official is responsible for the long-term management and preservation of preexisting and new collections subject to this part. Such collections shall be placed in a repository with adequate long-term curatorial capabilities, as set forth in § 79.9 of this part, appropriate to the nature and content of the collections.

And furthermore, that:

The Federal Agency Official shall ensure that the Repository Official makes the collection available for scientific, educational and religious uses, subject to such terms and conditions as are necessary to protect and preserve the condition, research potential, religious or sacred importance, and uniqueness of the collection.

By extending NAGPRA past its legal authority into repatriating objects not associated with graves, the Federal government is breaking its own laws, which mandate they preserve and facilitate access to archaeological collections from their lands. The Forest Service could of course choose to transfer the Mummy Cave assemblage to a Native-operated curation facility that meets ARPA standards and facilitates collections research, and I would fully endorse that action as a positive step toward Native American autonomy. However, nothing in NAGPRA allows for such an action, and trying to force the law into actions it doesn’t support cheapens NAGPRA and only confuses the repatriation process.

Perhaps most importantly, let’s not forget that other Native American groups have a stake in these collections as well, and in my view the Kiowa in particular. Wyoming has a long history of use by dozens of Native peoples, the evidence for which is found most directly in the archaeological record. There are several such groups whose presence in the state preceded historical documentation that are routinely excluded from NAGPRA consultations in Wyoming. Repatriation of important archaeological assemblages effectively erases the history of these peoples in Wyoming, thereby diminishing their standing to claim ancestral remains from the state. Maybe some of these Tribes don’t care and would rather see the artifacts returned to whoever, as long as it’s not archaeologists. But certainly others do care and would appreciate a greater voice in the state. Regardless, the point of maintaining permanent archaeological collections is to preserve an unchanging record of the human past that remains resilient in the face of changing politics and opinions.

Meanwhile, Mummy Joe remains locked in a climate controlled cabinet at the BBCW, waiting patiently to return to a proper resting place. He’s been exhumed from his burial place, put on display, ignored by the Department of the Interior for 11 years, ignored by Tribal governments who failed to claim the remains in 2006, and now delayed in his reinterment while modern politics interjects its voice into the matter, complicating exactly what should and should not be reburied with him. In its original form, NAGPRA is a good law with clear direction, and we should perhaps return to those basics in order to resolve this lingering, long-overdue case. Mummy Joe deserves it.

Glad you wrote this. I hope it spurs some action. I think you hit on something that is plaguing modern tribal consultation. As you said, the feds have fought long and hard to develop relationships with the tribes. They are determined to maintain these relationships, especially in the wake of recent issues (i.e. DAPL). In order to do this, I think some agencies avoid disagreements at almost any cost. Or, even worse, delays decisions and determinations. They keep everyone in limbo, including the tribes. Consultation requires room for disagreement. For serious, upsetting discussions. Otherwise consultation becomes attrition. Like the dweeb who suddenly finds himself dating the star cheerleader; he’ll do anything to keep her happy, until eventually no one is happy.

If non-indigenous peoples excavate and remove items on a continent that does not belong to them in the first place yet still inhabit, NAGPRA does not and cannot go far enough, no matter non- indigenous systems of what is or isn’t valuable, including arrows and coprolites. Ideally any excavations done now and artifacts acquired in the past should be a domestic matter within the tribes when we choose to, which as you know isn’t done and if it is remains controversial, not one in the name of “discovery” by settlers and their institutions. As it stands, anything you have learned about us through archaeology you could have learned from us personally had your ancestors chosen a different path that didn’t impede your curiosity. This isn’t about speculative history or re-litigation- this is about what justice demands from a people and nation who have grown so strong on the blood and resources of my own, then come from that state of strength and privilege and investigate the people they’ve exterminated. We are all humans but archaeology is not a part of a common good. As fascinated as you may be by north america, it simply isn’t yours to plunder. You are free to do so on your own ancestral lands, however. We as indigenous people will respect your right to do so and consider it your own business. As for here, no amount or manner of moral delusion , no scientific sensibilities you concoct will ever give you or any other settler archaeologist the right. Sovereignty is about nation to nation with mutual respect. Why would you want to take more than you already have?