What makes for good TV?

I wrote recently about the successful series Ancient Apocalypse, which spent much of November, 2022 near the top of Netflix’s viewership rankings. The series was widely panned by archaeologists on the basis of its false claims and accusations of racist undertones, but I suspect there was some underlying jealousy in the mix too. How could Graham Hancock, an interloper to archaeology, possibly garner this much attention and success when working archaeologists struggle to explain what they do even to family over Thanksgiving dinner?

To my eyes, the series’ widespread appeal can be attributed to characteristics highly valued by audiences that professional archaeologists struggle to deliver: mystery and discovery. Everyone loves a good mystery, and the human past is full of them. However, it is archaeologists’ jobs to solve those mysteries, or at least critically examine them enough to draw the curtain back and reveal the underlying processes responsible for creating them. A mystery solved is a mystery no more, and that’s just no fun to watch.

Discovery was a cornerstone of archaeological inquiry in the age when pipe-smoking Englishmen staged expeditions to exotic lands, employing locals to exhume the ruins of civilizations long forgotten. But those days are over, and furthermore laden with colonial undertones very much not in fad today. I think most archaeologists still get a thrill out of making genuinely new and exciting discoveries; after all, everyone needs an answer to the question “what’s the coolest thing you’ve found?” However, pursuing discovery for its own sake is undoubtedly considered gauche among most modern practitioners and frankly, amazing discoveries don’t often happen.

So that leaves most archaeologists with the quite scholastic task of explaining the past as a means of engaging non-professionals, and unfortunately that just doesn’t sell very well. Most people turn on their TVs to be entertained, not do extracurricular homework. However, there remains a small number of anthropologists with the ability to at once carry the torch of mystery and discovery while proving that you don’t have to sacrifiice scientific rigor for large-scale public engagement. Of those, Lee Berger is the best.

Who is Lee Berger?

Lee Berger is an American-born paleoanthropologist who has worked out of South Africa’s Witwatersrand University since the late 1980s. He has spent the last 30 years working primarily on fossils of human ancestors who lived in South Africa during the last 3 million years, finding them, describing them, and publishing them in some of the world’s most prestigious scientific journals.

Berger is a prolific researcher, having contributed to somewhere around 200 publications and written several popular books. Like most scientists, most of Berger’s work pertains to niche aspects of his discipline read by a small group of super-nerds, like tooth growth, dating techniques, and femoral neck morphology. Such studies are the meat and potatoes of bona fide working scientists, and most scientists spend their entire careers producing studies like these and these alone. However, Berger has also produced some of the most impactful, widely cited paleoanthropology research in the last 20 years. Between 2010 and 2015, Berger published not one, but two new hominin species (i.e., ancient human ancestors) from newly discovered paleontological sites in South Africa. Most paleoanthropologists discover 0 to 1 new species of human ancestor in their careers, so Berger’s 2 in a decade streak is unprecedented.

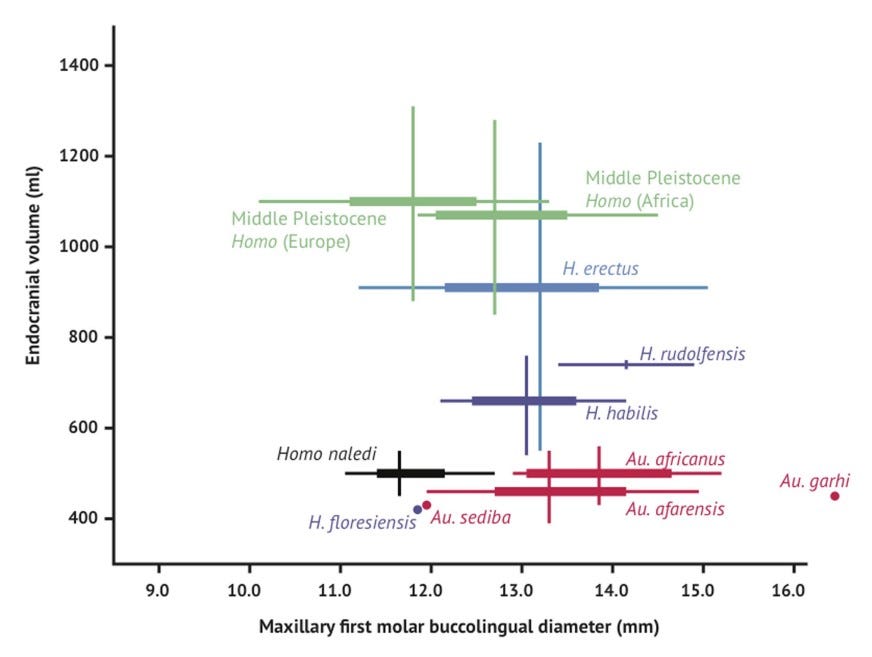

In 2008, Berger’s 9-year-old son discovered the first fossil clavicle (collar bone) of what Berger would come to call Australopithecus sediba, a newly-defined, 2 million year old member of the genus (made famous by “Lucy”) that lies just lower on the family tree from our own genus Homo. The exact placement of sediba in our family tree is still being parsed, but my take-home from the species has always been simple: our bodies, which are uniquely equipped to walk on 2 feet and conduct fine work with our hands, evolved well before our big brains. Sediba is a good example because it had a full capacity for bipedalism and a human-like hand, but its brain remained 1/3 the size of our own, suggesting that it could be directly ancestral to those members of the genus Homo that eventually evolved large brains and into modern humans.

Late in 2013, Berger posted an enigmatic call for workers on Facebook, asking that applicants be skinny, hold an advanced degree in archaeology, have caving experience, and be willing to travel to South Africa immediately. Less than two years later, Berger and his team of small, female cave enthusiasts emerged from Rising Star Cave with a new hominin species called Homo naledi. The Rising Star Cave system turned out to be the most dense deposit of hominin fossils ever discovered in Africa, which gave Berger and his large team of collaborators a detailed understanding of naledi’s anatomy. Like sediba before, naledi exhibits a mosaic of very old traits (like a brain 1/3 the size of modern humans) and very modern ones (like a fully evolved foot). Thus, it was shocking to find that naledi, with its tiny brain but human-like anatomy, lived only around 275,000 years ago, suggesting they may have interacted with their much larger-brained cousins Homo erectus and potentially even some of the earliest modern humans.

Alongside his discoveries, Berger is known for his eagerness to employ mass media and open access publication to promote and disseminate his work. Berger is a natural on camera, maintaining a baby-faced visage well into his 50s and speaking publicly with the cadence of a protestant minister, perhaps a holdover of his upbringing in the American south. Berger had a head start in this regard, having been employed by a Georgia news station in his early 20s before embarking on his career in paleoanthropology. Accordingly, Berger seems to have an appreciation for the skill it takes to distill difficult ideas into easily digestible stories, and in his own work he does it well. While Berger’s eagerness to engage the public has drawn global attention to his work, it’s also the aspect of his career that has gotten him the most flack from his peers.

Is There a Problem with Oversharing?

Berger has been criticized by some colleagues for embracing public science, most visibly in a 2016 New Yorker profile published after the discovery of naledi. In the piece, Berger is depicted as someone who, above all, wants to be famous and has spent much of his life seeking attention from his peers. The piece goes so far as to suggest that Berger’s focus on public messaging detracts from his research quality, which is characterized as slapdash and careless. In the piece, SERIOUS™ paleoanthropologists describe the discovery and publication of naledi as “just another headline-grabber”, “more spin that substance”, and dismiss its significance by claiming “it’s the armwavers who command attention.”

In some ways, I get it. Berger excavated and published naledi at an unprecedented pace of under two years and did so under the watchful eyes of documentary film crews and international media outlets surely eager for a sensational story. It must be hard for those who have devoted large portions of their careers to the excavation, analysis, and publication of a single fossil specimen to watch Berger produce high profile research in 1/4 of the time. And to be fair, Berger’s reputation for announcing shocking finds prior to rigorous interrogation of the evidence is sometimes warranted. Most recently, Berger announced for the first time in a public talk in Washington, DC that naledi likely commanded the use of fire, a discovery perhaps best announced via peer reviewed publication.

That being said, Berger has what I can only describe as a radical approach to open science, publishing his first naledi finds in a free, open access journal, allowing unprecedented access to his sites and collections, facilitating specimen reproduction through digital files of 3-d models, and a host of other gestures that indicate a true devotion to breaking down barriers to scientific access. If you doubt Berger’s claims, as many have, then it’s on you to prove him wrong because he provides you all the data necessary to do it. It’s probably surprising to those outside the discipline, but this open approach is very much at odds with the prevailing culture of paleoanthropology. Of anthropology’s various subfields and branches, paleoanthropology contains some of the biggest egos, highest stakes, and most prestige, and has thus garnered a reputation for being a particularly toxic research domain veiled in layers of secrecy. Berger’s open science approach is a quiet revolution in paleoanthropology, and all he had to do was create it and let the rest of the field expose itself for what it had become: a discipline mired in spiteful, jealous attitudes stuck it ways that stultified its own progress.

In Berger’s inquisition we see clearly the inherent contradiction at the heart of anthropology’s public image problem. Although we desire global visibility and a place in the mass media canon, we criticize those bold enough to step into that role as ‘attention seeking,’ the subtext being that media visibility comes only at the expense of scientific rigor. But being famous isn’t easy, and we should support and promote those in our discipline with the skills to do it well, not turn our noses up at their success.

Why Berger?

Berger has by no means languished in obscurity. His awards and memberships in various prestigious societies are numerous, and he has been featured regularly on television series and documentaries. However, he has yet to crossover into mass media of the Netflix or Hulu sort, the types of global platforms that tens of millions of people tune into and that people like Graham Hancock dominate but professional anthropologists struggle to attract. I think Berger is the right anthropologist to step into that sort of global public notoriety.

First, Berger certainly checks the mystery and discovery boxes so appealing to audiences that tune into archaeotainment. His new hominin discoveries speak for themselves but even his analytical work on existing fossil collections demonstrates a penchant for discovery. For instance, in his first truly impactful study, Berger argued that the Taung child, the 2.8 million year old type specimen for Australopithecus africanus, was deposited in the refuse heap of an eagle. Before Berger, it was argued that the Taung fauna was amassed by Australopithecines, suggesting that they were brutally efficient hunters who dragged a menagerie of South African animals back to their cave lair to hack at them with bones and antlers for their meat and brains. Berger showed quite the opposite. Australopithecines were relatively small, vulnerable primates at the lower end of a harsh African status hierarchy, subject to predation even by eagles. The study is a great example of how some of the largest discoveries in anthropology lay right under our noses, waiting for an individual with novel insights about the past to uncover them.

As for mystery, there is little more mysterious in modern anthropology than the existence of Homo naledi. Netflix gave us a series about a mysterious ancient civilization lost to the rising waters of the post Ice Age world for which there is no evidence. Berger gave us a population of small-brained hominins from a cave in South Africa that likely co-existed with our own species in the not so distant past, supported by ample evidence. But if I was asked 10 years ago to pick the more unlikely scenario, I would have chosen Homo naledi. How did such a species survive for over a million years alongside much larger brained hominins? Why did they diverge from the rest of the larger-brained hominin lineage in the first place? And why did they disappear? I find these mysteries far more compelling than anything I viewed on Ancient Apocalypse, and if interpreted in the right way I suspect much of the general public would as well.

I also have to admit some bias here because I feel a certain kinship with Berger, though we’ve never met. We’re both southern Eagle Scouts that grew up hunting arrowheads who went on to study the past. Like me, Berger was likely 1 of a very few of his bible belt classmates to believe in evolution by natural selection. Like me, Berger floundered a bit in a less than prestigious state school before finding his direction. And like me, Berger seems to get a kick out of ruffling the feathers of elite, establishment institutions and individuals who derive their worth from academic pedigree and elite decorum rather than merit; the types of people (New Yorker journalists perhaps) whose ivy league admissions letters were signed by Congressmen. Perhaps it’s just a base, homophilic impulse on my part, but I’d love to see Berger on my Netflix home screen.

Ultimately, the arc of Berger’s career serves as a great example of how to maintain curiosity and wonder for the past that I find universally compelling. I sometimes consider it when I get bogged down in administrative duties or research minutia and lose track of why I loved studying the past in the first place. Berger’s career is a good reminder that there are still genuine mysteries in the world and amazing discoveries to be made, and if you remain curious, inquisitive, and open to the truly phenomenal, you might just find them too. And THAT’S the sort of message that people pay to watch.