The Repatriation Project

Propublica is an independent media outlet whose stated goal is:

To expose abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust by government, business, and other institutions, using the moral force of investigative journalism to spur reform through the sustained spotlighting of wrongdoing.

In 2022, Propublica began The Repatriation Project, an investigative journalism series focused on implementation of 1990’s Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The story wrote itself. The Federal government had been negligent in facilitating Native American repatriation for decades, allowing human remains from their lands to languish in repositories and museums who held them in trust. At the same time, Native American attitudes toward repatriation evolved to subsume much of the archaeological record, a result of increasingly militant political views grounded in decolonization. All Propublica had to do was roll up their sleeves and dive in.

But those are not the stories they wrote, choosing instead to lambast museums and academic institutions for their uniquely awful failure to implement NAGPRA. Over the course of a year, Propublica published over a dozen journalistic pieces ranging from critical evaluations of museum NAGPRA compliance to hit pieces on individual academics. Together, Propublica’s coverage presents a damning portrait of American museums and anthropologists, who have together conspired to evade a decades-old mandate to return Native American remains and cultural items to living descendants.

The Repatriation Project seems to the outside observer like the kind of important investigative journalism sorely missing from today’s media landscape. The problem, unfortunately, is that the entire project is built upon a great manipulation of truth and history intended to manufacture public outrage surrounding NAGPRA implementation. That outrage was leveraged in 2023 to pass sweeping changes to NAGPRA regulations, a move that has placed the entire American archaeological record in limbo while institutions struggle to understand its implications. Here, I’ll expose that false narrative and suggest why, in the face of a far more interesting story, Propublica chose to attack America’s academic institutions and museums.

The False Narrative

The false narrative at the heart of the Repatriation Project goes something like this: American museums and academic institutions utilized a NAGPRA loophole to withhold human remains for decades that should have been repatriated to Native American Tribes. The grain of truth in Propublica’s reporting is that yes, most museums and repositories currently hold items that Native American Tribes are now interested in obtaining via repatriation. But why they have those items is more complicated than Propublica acknowledges.

Many items remain in storage because they were determined to be unaffiliated with living people. NAGPRA originally intended to provide living Native Americans with a means of repatriating the remains of their direct ancestors collected since the late 19th century. In most cases, direct ancestors could be reasonably identified for the last several hundred years based on a combination of location, oral history, biological characteristics, and archaeological evidence. NAGPRA recognized until recently that remains older than at most 2,000 years could not be affiliated with modern people because they were simply too old. All cultures are born, decline, and eventually fade from existence. Most of the material culture that archaeologists study belonged to those ancient cultures whose members may have been genetically ancestral to living people in the grand arc of New World prehistory but only tenuously related to modern people culturally, if at all.

The unaffiliated designation is now cited as a NAGPRA ‘loophole’ by Propublica, a flaw in the legislation that Congress never intended. But unaffiliated remains were a central feature of NAGPRA implementation until this year’s revised NAGPRA regulations passed, agreed upon by Congress, academics, Federal officials, many Tribal representatives, and even reaffirmed by a 2002 Federal court decision surrounding the controversial Kennewick Man repatriation case. Unaffiliated was in the regulations for 30 years, and I find it hard to believe it was simply an administrative oversight.

In 2010, Federal officials elevated the regulatory importance of ‘geographic affiliation’ in a first effort to eliminate unaffiliated remains from NAGPRA, a move that has since resulted in removing unaffiliated from the regulations altogether. Geographic affiliation claims that all human remains and material culture, regardless of age, are affiliated with whomever occupied the lands from which those remains were discovered within the last couple hundred years. It is effectively a religious belief that claims all Native Americans were created in their historically documented homelands at the beginning of time and haven’t moved since. At the least, geographic affiliation is fundamentally untrue. At worst, geographic affiliation results in egregious missteps in the repatriation process. This is how, for instance, Siouan speakers who arrived to the western Great Plains within the last 200 years can hold legal claim to the 500 year old ancestral remains of the Pawnee, who no longer occupy those ancestral lands and whose ancestors were fierce rivals of the Sioux. Maybe unaffiliated left some remains sitting in repositories, but the alternatives can lead to legal warfare.

Not all human remains sitting in storage are unaffiliated. Many of them were culturally identified long ago and never claimed by Native American Tribes. In the 90s, some Tribes thought NAGPRA was odd and didn’t want to participate in it, and even now not all Tribes are eager to make claims on remains with ambiguous cultural affiliation. Even remains claimed for repatriation often don’t get repatriated because the claimants never bother to obtain them. Some Tribes place dozens of claims on orphaned human remains with ambiguous cultural affiliations, but between the rush to repatriate and rapid turnover in Tribal leadership, many claims are never repatriated. In either case, human remains simply sit in the facilities where they have for decades, in a liminal state between research prohibition and repatriation.

One final reason that human remains still lie in storage facilities is that many facilities don’t own their collections but hold them in trust for the Federal government. In these cases, Federal agencies are ultimately responsible for NAGPRA compliance. These arrangements are especially common for facilities that hold remains from public lands in the American West. Many Federal land managers like the Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, and U.S. Forest Service have simply not complied with their obligations under NAGPRA. Ironically, the Department of the Interior (DOI) is especially negligent in their NAGPRA duties in the cases of which I am aware. I guess if you write the rules you feel less obligated to obey them. Propublica acknowledges that the DOI holds over 3,600 remains, but it appears as though they only counted remains held in DOI facilities, not those held in trust by other facilities.

I’m not claiming museums, academic institutions, and repositories are blameless, and there are surely some that neglected their duties under NAGPRA. But I also don’t think they are uniquely culpable for the existence of Native American remains in their storage facilities. Between categorization of human remains as unaffiliated, failure to claim or repatriate human remains by Tribes, and the negligence of Federal land management agencies to uphold their end of the process, there is plenty of blame to go around.

That leaves me wondering why Propublica wrote the story they did. Why, out of all the narratives that could have been told about repatriation, did they choose to single out museums and academic institutions in the repatriation project? (puts on tin foil hat) Allow me to speculate.

The Motive and Means

I think Propublica received their talking points for the Repatriation Project directly from a group of activists associated with the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Association of American Indian Affairs (AAIA). I should be clear that I don’t know how Propublica coordinated their messaging, only that the content and timing of their reporting is too similar to DOI policy changes and AAIA activist initatives to be a coincidence.

Also, the motives are pretty clear. In service to the DOI, the Repatriation Project stoked public outrage regarding NAGPRA implementation, thereby manufacturing the public consent needed to pass sweeping changes to NAGPRA in 2023. It also deferred blame for repatriation failures from the Federal Government to museums, academic institutions, and repositories, thus obscuring government accountability for NAGPRA compliance.

Propublica’s motives for working with the DOI are equally obvious. For one, they obtained access to the National NAGPRA Program’s repatriation database for use in a widely publicized interactive map. Moreover, a tidy story about institutional corruption is Propublica’s brand, and once the narrative was created, NAGPRA’s revised regulations were almost certain to pass. When they passed in 2023, Propublica leveraged the victory extensively in their news coverage. This sort of results-based journalism is the bread and butter of activist news outlets, especially large outlets like Propublica that rely on charitable donations to sustain their $34,000,000 a year operation budget.

In 2023, in part because of the attention from ProPublica and tribal pressure, more ancestral remains were returned than at any other point since the law’s passage in 1990.-Hudetz and Jaffe in Propublic, 2024

We don’t have to speculate wildly about how this collaboration occurred, which appears to have taken place primarily during the Association of American Indian Affairs’ (AAIA) annual repatriation conference. The AAIA has existed 100 years and in that time has done alot of good work for Indian Country, raising money to fight youth violence and promote child welfare, running summer camps, and other initiatives leading to positive outcomes for American Indian communities. In the last decade, the AAIA has taken a more activist turn alongside the adoption of a decolonial worldview, one focused less on creating immediate positive impacts and more on Instagram activism best characterized by the sloganeering of their #everythingback movement. Expanding repatriation has been a key component of #everythingback.

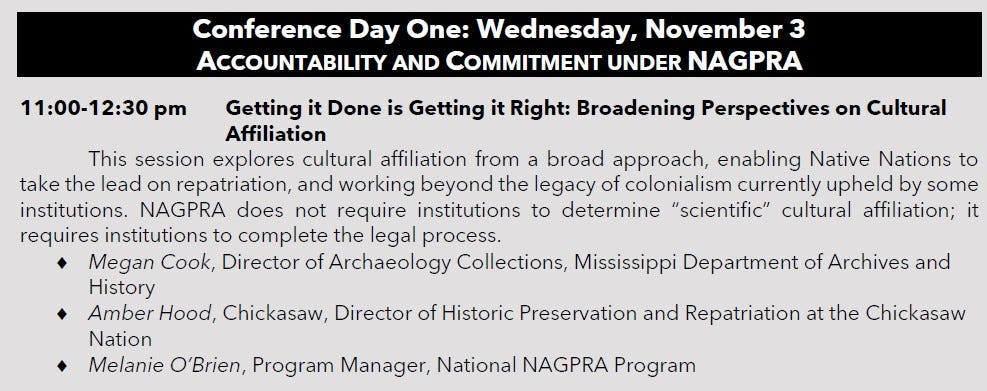

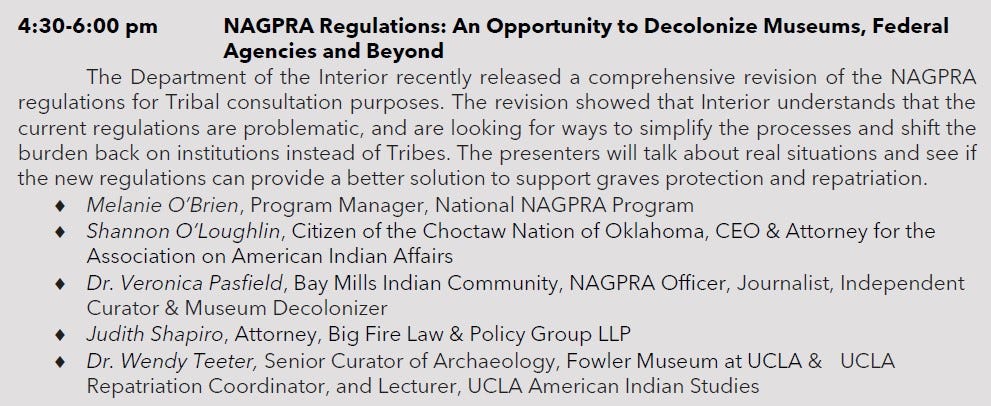

In 2021, the 7th annual repatriation conference was held virtually during three days in November. The conference agenda serves well as an outline for the radical NAGPRA regulatory changes to come, both in content and authorship. The agenda is stacked with DOI officials, including the entire staff of NAGPRA’s National Program office. The NAGPRA review committee, who is responsible for resolving contested NAGPRA cases, even held one of their public meetings at the conference. The NAGPRA National Program Manager, Melanie O’Brien, appears in the program at least 3 times, in symposia titled NAGPRA Regulation: An Opportunity to Decolonize Museums, Federal Agencies, and Beyond and Getting it Done is Getting it Right: Broadening Perspectives on Cultural Affiliation. Here, we see clearly the origin of 2023’s NAGPRA overhaul.

One of Propublica’s key repatriation informants is the AAIA’s Chief Executive, Shannon O’Laughlin, a one-time Joe Rogan Experience guest and go-to spokesperson for comment on the corruption of American museums. O’Laughlin joined the non-profit world after serving as a member of the Federal NAGPRA review committee in 2013 and the Cultural Property Advisory Committee in 2015, the kind of public to private transition made by many who hear the siren song of non-profit salaries well into 6 figures.

The Result

I could go on, but you get the point. The small number of people driving NAGPRA’s 2023 regulatory changes all know each other. They have all worked for and promoted each other’s organizations, attended the same conferences, and probably had a few good laughs at the expense of archaeologists over margaritas in a quaint Santa Fe cantina. Their relationships are not so different than any other professional network. Their work just happens to be dismantling American archaeology rather than, say, dentistry.

In that light, Propublica’s big untruth wasn’t really theirs at all. AAIA devised a false and misleading narrative about NAGPRA while the DOI turned that narrative into Federal regulations and Propublica delivered the messaging. That sort of vertically integrated policy making between government, media, and business (or non-profits) is exactly the sort of back channel work that gets things done in American politics. But it’s also bad for democracy, especially when overtly tied to a radical decolonization agenda antagonistic to liberal democracy in the first place. For the Repatriation Project, Propublica seems to have spent less time “exposing abuses of power by government” than serving as the government’s hand maiden.

Ultimately, I don’t envision the collaboration between the DOI, Propublica, and AAIA as some kind of nefarious conspiracy. The small group of activists pushing for revolutionary change in American repatriation are just friends and colleagues invested in the same political agenda. They talked alot, coordinated messaging and timing, exchanged quotes for media outlets, and generally supported each other in a common goal. And I should also admit that I like Propublica, who generally do important reporting work. I just think they missed the mark with the Repatriation Project.

It went wrong when their conversations became siloed within an echo chamber of agreement. At some point, everybody agreed to exclude dissenting views from the conversation. There are no archaeologists invited to the repatriation conference nor employed by the National NAGPRA Program. Propublica did not interview anybody who helped draft NAGPRA in the early 90s to understand their intent nor anyone skeptical of their narrative. And the DOI, when forced by regulatory procedure to consider alternative views, responded to critiques with rambling defenses of their policies that often concluded with the legalese equivalent of “we’re the Federal government and we’ll do what we want.”

Despite the appearance of widespread public support for the new regs in popular media outlets, I have yet to speak to a single archaeologist, museum professional, or even Tribal member who full throatedly supports them. Most institutions probably responded the way mine did, by allowing their legal team to respond to media requests with a generic expression of support for fear of retribution by the DOI. The fact is, they are bad regulations inspired by false pretenses, at once confusing, internally contradictory, unrealistic, ideological, unconstitutional, and generally catastrophic for heritage management in the United States. This is already becoming clear and will only become more so in the coming years unless somebody steps up to challenge them in court. But more on that later.

Very well said! Thanks

Again, excellent writing on a complex topic. Brave, too. Thank you.