The Nimerigar

The little people did this to me, I think as I roil in damp bedsheets, at once freezing and feverish. I’m 6 hours into a 103 degree illness vomited into my vascular system by an embedded tick. Cruelly, within my belly button.

The Eastern Shoshone maintain oral myths about a race of little people, the Nimerigar, that live in the high mountains of Wyoming. They play tricks on people, stealing possessions and shooting poisoned arrows from their tiny bows into their enemies in defense of their ethereal mountain home.

Some Shoshone believe that rock image sites, those pecked and scratched remnants of Wyoming’s artistic past, are especially important to the Nimerigar. The Sheep Eater Shoshone of Wyoming’s interior used rock image sites during their vision quests, sitting before the panels for days waiting for spirit guides that might imbue them with sacred power. The little people were the stewards of these sites, visiting supplicants during their hallucinatory quest and guiding them into the rock to commune with the strange theriomorph creatures depicted in many rock images, half men-half beasts.

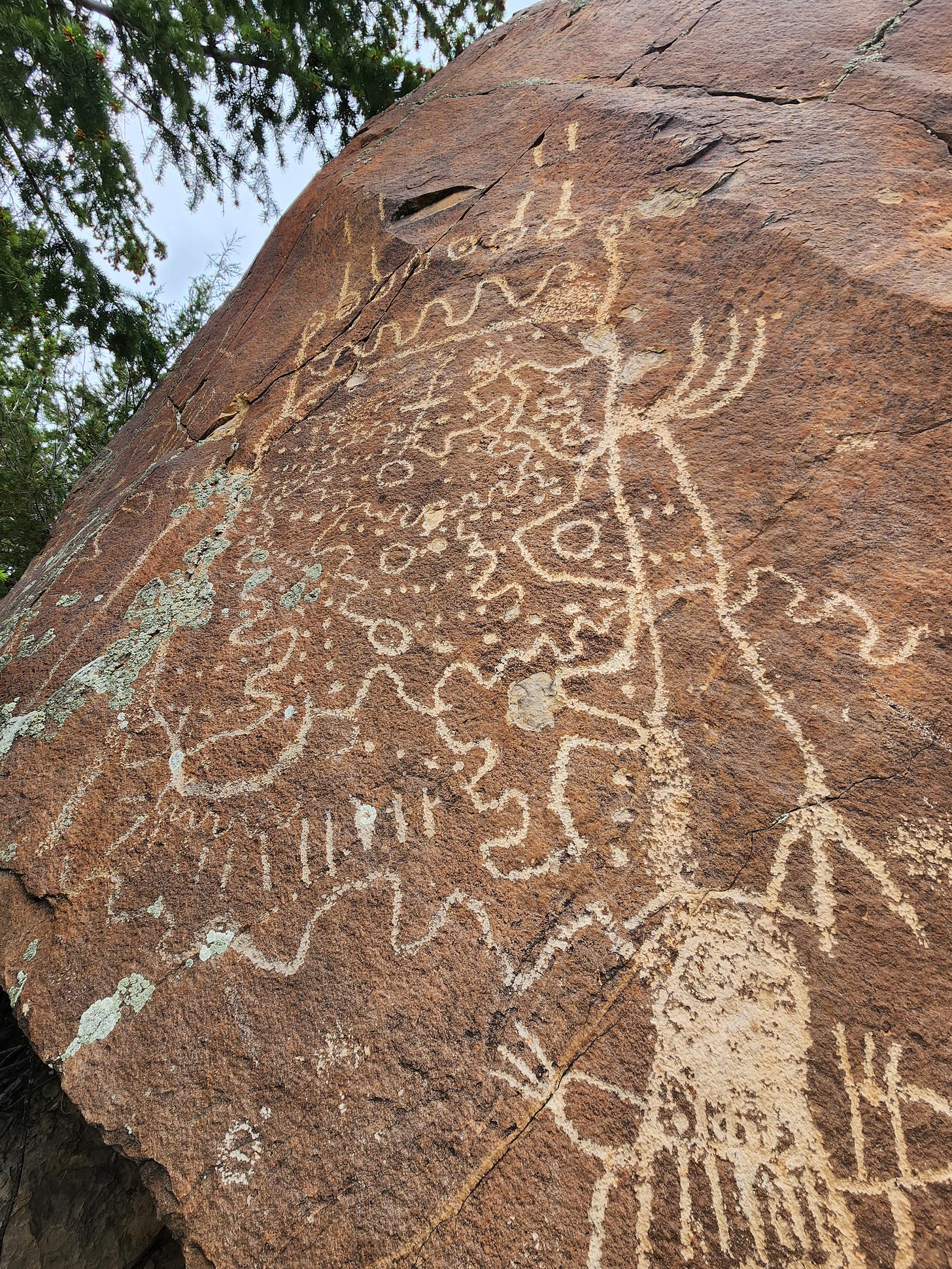

It was a rock image site where I picked up the tick fever. The Torrey Lake petroglyph site is a complex of striking rock image panels scattered among boulders and cliff faces in the northeast foothills of the Wind River Mountains. With few exceptions, the panels are pecked in the Dinwoody Tradition style of rock imagery. Dinwoody is world-renowned for its vivid, hallucinatory imagery, representing a diverse pantheon of animals, human-animal hybrids, and other strange beings that together depict a cohesive mythical world localized to the headwaters of the Wind River. The people who created Dinwoody rock imagery, perhaps the distant ancestors of the Sheep Eaters or yet another unknown ancient culture, obviously shared a rich mythic tradition now left depicted on the patinated canyon walls of the Wind River and its tributaries.

Our visit to Torrey Lake was largely political, a brief tour with some legislators to share some of Wyoming’s archaeological crown jewels. As I cursed the wretched arachnid that spewed its illness into my system, my ire turned to the little people. Was our intent too profane for this sacred ground? Did I not pay sufficient respect to the Nimerigar’s stewardship? Regardless of my folly, the little people’s poisoned arrows got me, delivered directly into my abdomen via the serrated maw of an infected tick.

My fever broke for a brief while around 18 hours into the illness. In a moment of perceived lucidity, I abandoned the notion that I had been cursed by the little people for what I deemed to be a more plausible explanation. I imparted the grand theory to my increasingly concerned wife in a dazed confusion, a theory I’ll lay out here for posterity.

Tick Fever

Dinwoody Tradition rock art is globally renowned for its uniqueness. No other rock art tradition in Wyoming, and few in the Americas, contains such a fantastical array of imagery. Dinwoody is most often explained as having been inspired by hallucinatory experience, depicting the types of wild beings one might dream up when their mind is unencumbered by the strictures of the physical plane.

Today, any undergrad in the Red Rocks parking lot could list for you a couple dozen ways to induce such experiences, but in the past one’s options were limited. Famously, some American cultures had access to hallucinogenic plants out of which they developed elaborate spiritual rituals. The peyote, ayahuasca, and datura using peoples made famous by podcast bros who have, of course, also started marketing the experiences to wealthy westerners in need of spiritual healing after their divorce.

But hallucinogenic using cultures were rare in the human past, and most sought enlightenment in more prosaic ways. Starvation, fatigue, self-induced pain, digit amputation, sweat lodges, and my personal favorite, smoking so much tobacco that you throw up and kind of hallucinate a little. Whatever the means of liftoff, the end goal was the same. That one might enter a higher plane of existence, receive spiritual power, and return to share that power with one’s culture. In the ancient past, it might have been a revelation about animal behavior that increased hunting prowess. In the 60s, it was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Having just experienced some mild, fever-induced hallucinations myself, it occurred to me that intentionally inducing severe illness could be another means of achieving enlightenment. I didn’t return from tick fever with any revelatory power; I just hallucinated a swarm of cicadas in my ears. But had my fever stuck around another few days, then this newsletter might have taken a drastic left turn into spiritual self help. Those who experience brushes with death, whether they be illness or injury, often return from the experience to report a sense of spiritual awakening. “Seeing the light” as they would say in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

So here’s the idea. The headwaters of the Wind River have always been a tick-infested hellscape that also happens to be the most beautiful part of Wyoming. Whoever created Dinwoody rock art knew that and intentionally sought out places with a high likelihood of pathogen carrying ticks. They would allow the ticks to bite them, perhaps several at a time, and wait for the illness to take hold. Or in the parlance of a vision quest, wait for their spirit helper to arrive. If it did, the tick fever would persist for a few days, the stricken individual would hallucinate some crazy shit, and then they’d snap out of it one morning like I did. They’d record their experience as Dinwoody rock art (some of it does look a little “ticky”) and return to their group with tick power. The origin of Dinwoody Tradition rock art? You guessed it. Tick fever.

My wife stepped out of the bathroom to inquire, “Are you alright baby?” I laughed, rolled over, and pulled the sheets tight over my shoulders. “Not at all,” I responded.

In Retrospect…

It took a couple weeks to recover from the fever, and I’m probably still not fully there close to a month later. I’ve still got some muscle fatigue and foggy headedness, the symptoms you’d associate with the after effects of holding a fever for awhile. But I’m sober enough now to critically assess my fever dream of a theory. I think it’s unlikely but not impossible.

In argument against, we have no idea if ticks carried the multitude of diseases they do now in the deep past. The big two tick-borne illnesses in Wyoming are Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, an extremely dangerous bacterial infection, and Colorado Tick Fever, a severe if less lethal viral infection. I don’t know which I had, but it was likely Colorado Tick Fever. Ironically, these diseases and a slew of others are more common in the mesic eastern woodlands than they are in the arid Rocky Mountains of Wyoming and Colorado. Although tick-borne disease has increased recently as a result of mild winters, inducing hallucinations with tick-borne illness should have been way more common among eastern Indigenous groups than those in the west.

Moreover, intentionally contracting a tick-borne illness is really dangerous, and I’m not sure it could easily work its way into routine cultural practice. For instance, I read at some point during my feverish sojourn that 1 in 5 people who leave Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever untreated FREAKING DIE. And those who survive often suffer from lifelong after effects. Rites in which one receives spiritual power are universally associated with danger, but even amputating one’s own finger has a far higher survival rate than some tick bites. It’s not a cultural practice that you’d expect to last long.

On the other hand…if Colorado Tick Fever was the only illness present, then there might not have been much risk in contraction. And once infected, you’d likely be resistant to future infections. Under controlled conditions like a religious rite, intentionally exposing oneself at a young age to tick bites might actually help inoculate against infections at a more advanced, vulnerable stage of life. This is exactly the sort of cultural ecological adaptation that anthropologists dream about.

Also, the use of biting insects (or in this case arachnids) during religious rites is not unheard of among traditional people. Tribes in southern California and northern Mexico would eat live red ants during religious ceremonies as a test of fortitude and, presumably, to induce a pretty bad high in search of spirit helpers. And at least one Amazonian tribe forced young men to wear gloves filled with harvester ants as a coming-of-age ritual, a rite that resulted in severe illness. I am aware of no traditional groups that employed ticks in the service of their spiritual needs, but it’s possible they existed in the deep past.

All hand waving aside, I feel obligated to end with a public service announcement. Tick illness can be really serious and don’t take it lightly. This was the most severe illness I’ve ever had, and I’m still dealing with the after effects. It’s apparently more common than it’s ever been, and you have a decent chance of contracting something if you get bitten this year. So wear the strongest insect repelent on the market and don’t forget your belly button when you check for ticks.

Well done! (the writing, not getting the tick). Hope your recovery is full, does not sound like fun, but at least it inspired a good post.

Well, that was interesting. You can only imagine the puns running through my head, but in the interests of your ongoing recovery, I am just going to say that I’m glad you’re doing better, and perhaps you should be in touch with Larry Todd. He is Mr Tick as far as I’m concerned. If there is more to be learned about these little critters, Larry is the man!