Back in February I wrote about why Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist for South Africa’s University of Witswatersrand, should be the public face of the past, Netflix series and all. I didn’t know at the time that Netflix had already collected footage of Berger and his team, and during the last several months had put the finishing touches on a film describing research out of Rising Star Cave. Now Berger has the number 3 title on Netflix, titled Unknown: Cave of Bones. If you’re new to this newsletter, I suggest going back to read that post to understand why I think Berger, among all anthropologists, is best suited for mainstream public interpretation of the human past.

By some stroke of luck, timing, and no shortage of ambition, Berger and his colleagues have managed to at once make truly phenomenal discoveries, catch them on film, publish them in both peer-reviewed and popular media, and turn them into a popular Netflix documentary within the course of a single year. Here, I’d like to provide my thoughts on Cave of Bones along with the immediate, and altogether predictable response from the paleoanthropological community to Berger’s recent claims that Homo naledi, a small-brained 250,000 year old human cousin, controlled the use of fire, produced the world’s earliest rock images, and ritualistically disposed of their dead in the dark recesses of Rising Star Cave.

Art and Graves and Tools, oh my

First, let’s review what they found and what reviewers had to say about it. In early June 2023, Berger and colleagues published 3 papers in the journal eLife that report intentional burial and rock art from Rising Star Cave’s Homo naledi inhabitants, and synthesize their evolutionary implications. They have additionally, in public talks and in passing reference, reported the controlled use of fire by naledi. These discoveries both extend the timelines for intentional burial and artistic expression by thousands of years and elevate naledi from an enigmatic, small-brained human cousin, to a creature with an early capacity for human-like behaviors.

The 3 burials reported by Berger and colleagues are especially impactful, and even more so if the small stone object associated with a naledi child’s hand is a tool placed with it upon burial. Until this point, intentional burial has only been unambiguously documented among modern humans. These burials would extend the practice into a different species and at least 150,000 years back in time. And if the lightly abraded stone detected via CT scan in the child’s hand is indeed a tool, it would be the first time that a stone tool has ever been found in the literal hand of an extinct hominin. An astounding discovery. Reviews for this paper were pretty scathing, claiming that the study should have spent more time discussing the nuances of how bodies fall apart once they are deposited and decay, questioning their field and lab methods, nitpicking graphics, and generally claiming that it does not “meet the standards of the field.”

I disagree. I think the study was well-executed, used novel methods, and is reported adequately enough to convey what are obviously burials. I’ve excavated a fair number of burials at this point, and had those features been encountered in a more recent context there would be no question regarding their validity. It’s just….obvious. I suspect most of the reviewers work in the deep past and have never seen a burial in the ground, so perhaps they can be forgiven for not knowing what they look like.

One scenario considered neither by Berger nor the reviewers is secondary interment, and I think it’s an option worth considering. I just excavated one a week ago in which we discovered a fully articulated hand associated with the disarticulated partial remains of a single individual stashed under a boulder on a high ridge in western Wyoming. Such situations are not uncommon among hunter-gatherers in the recent past, where individuals were left to decompose in open air settings and what was left of their remains collected later for interment in a secondary location. Some body parts remain articulated and others not. Fragmentary bodies would certainly have been easier to transport through the narrow chute used to access the Dinaledi chamber.

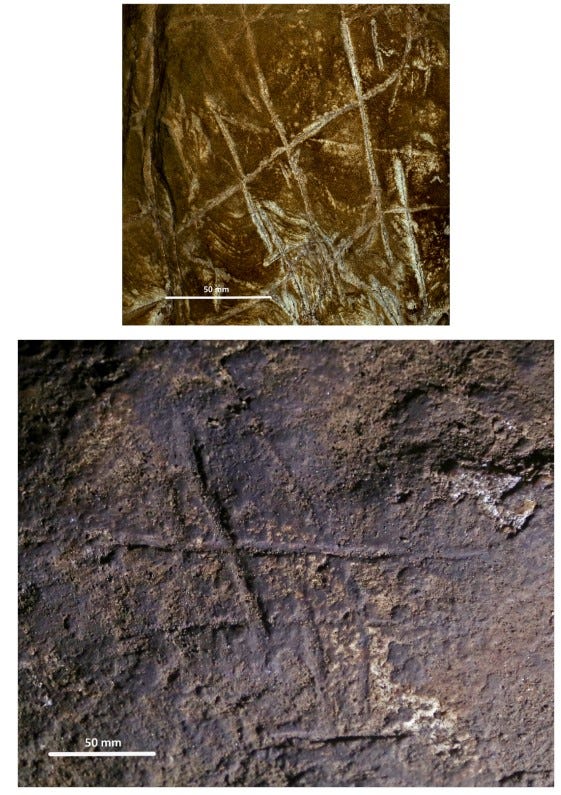

I would say that I’m less impressed by the rock engravings, but then I’m a pretentious snob for the visual arts. Let’s just say they’re no Chauvet Cave. Unlike the reviews of this work, I totally believe that the cave walls are modified and that those modifications were Naledi’s work. But like Neanderthal “art” reported before, I think it’s a stretch to claim that simple hashtag etchings are indicative even of simple abstraction, much less artistic expression. Unprecedented? Sure. But even bears scratch around on the insides of their dens and nobody’s hailing those as an abstract expression of their ursine minds.

These discoveries underlie the narrative in Cave of Bones, seeding the film with the mystery and discovery necessary to produce good archaeotainment. So did they pull it off?

Cave of Bones

I went into Cave of Bones expecting to see an informative if dry look into the discoveries that put Rising Star Cave on the map as one of the world’s most important archaeological sites. Ironically, anthropologists aren’t typically that good with people, and documentary filmmakers often struggle to deliver anthropology’s most important messages. So I tempered my expectations.

But the film is really great and delivers far more than I anticipated. Cave of Bones primarily features interviews and candid footage of Berger and his colleagues at work, oftentimes catching telling interpersonal interactions that add character depth seldom seen in scientific documentaries. Berger is obviously well-liked by his colleagues and staff, so when he announces he’d like to traverse the tiny ‘chute’ to enter Dinaledi Chamber for the first time despite his large stature, his cave guide is happy to help if also lamenting what will surely be “a long day.” And it’s hard not to laugh at colleague John Hawkes’ obvious anguish as Berger gingerly perches the cranial vault of a priceless Naledi specimen on several pieces of packing foam to get just the right camera shot into its eyes. Berger knows the value of a great image. Catching these sorts of interactions elevate those in the film from a group of scientists to a true ensemble of characters.

Beyond the live shots, Cave of Bones is beautifully produced, using dreamy, animated reconstructions of naledi life set to an original soundtrack to interpret the 250,000 year old events at Rising Star Cave. The animations neither brutalize nor romanticize naledi, depicting our human cousins as obviously distinct in form and behavior, but possessing the seeds of a human-like capacity for culture.

Most importantly, the film delivers that profound, if hard to capture message that every great intro to anthropology class should deliver: we are all one species united in our capacities for love and grief by some common ancestor deep in the African past. A scene featuring colleague Augustin Fuentes comes to mind, where he is filmed playing with a group of monkeys, discussing the roots of human behavior we can and cannot see among our distant primate cousins. In this way, the film is much more than a documentary about a sensational discovery, but an effective distillation of anthropology’s most important ideas.

I could nitpick the film for stretching interpretive limits or leaning a little too heavily on melodrama, but honestly there’s no need. It’s a great movie for any genre, and certainly one of the best anthropological documentaries ever made. Others disagree.

The Response

In February, I characterized paleoanthropology as among the most spiteful, jealousy-fueled scientific disciplines to exist. I wish I could say the response to Berger’s recent discoveries out of Rising Star Cave elicited a more civil, or perhaps even supportive response, but from my quiet corner of Twitter that didn’t appear to be the case.

Some appeared primed to dismiss the film at the outset, if later complementary:

While others are far more dismissive of Berger and colleagues’ work:

Or suggest that their work should never have been released to the public in the first place:

Notably, the general public seems to be enthralled by the film, with even the godfather of fringe, Graham Hancock, praising the film on his massive platform:

Berger probably isn’t thrilled to land a Hancock endorsement, but it’s a big deal to millions of people who tuned into Ancient Apocalypse and, as I’ve argued, anthropology has been way too hard on Hancock as well. I’m not sure it’s in paleoanthropology’s best interest to find itself again at odds with such a successful and universally loved film as Cave of Bones. Even if they have qualms with the content of Berger’s work, the dismissive, mocking tone of their response is an awful look for a discipline that lives and dies through public engagement.

Publishing for the Public

I have no doubt that Berger and his colleagues felt pressure to publish their discoveries quickly, ahead of a pending Netflix documentary (and book!) accompanied by the strict deadlines of the entertainment business. In their rush, perhaps the researchers decided to forego some of the more detailed analyses suggested by reviewers.

But truthfully, I suspect that Berger and colleagues could have labored over the Rising Star discoveries for years, excavating their finds grain by grain and meticulously addressing each critique, only to arrive in the same place they started: faced with a litany of new critiques attempting to obstruct publication. To many in the paleoanthropological community, Berger can do no right. These are phenomenal discoveries, and withholding their publication until they were subjected to an additional barrage of analyses would have only withheld them from the public longer while nominally improving their quality. I find it hard to fault Berger for publishing what they know right now, understanding that surely further studies are waiting to emerge from this work.

In my experience, getting published in paleoanthropology has alot more to do with the network to which you’ve attached yourself than the quality of your scholarship. It’s a small world and there’s only so many fossils to go around, so even if the review process is anonymous it’s no secret whose work you’re reviewing. If you’re not in the club (the Max Planck Institute apparently?), then good luck. You’ll always be faced with claims that you’re not meeting some unspoken and nebulous “standards of the field,” as if those exist. Berger and colleagues’ willingness to say to hell with it and publish their research in a (gasp!) timely manner is exactly the right way to deal with obstructionist academics.

Even if Berger is wrong, is it really such a big deal? Critics act as though quickly disseminating exciting finds to an eager public somehow cheapens their value, as if studies that have taken decades to compile haven’t also been wrong. They also behave as if letting non-sanctioned ideas escape the confines of academia forever damn the discipline to wrongthink, as if responses, critiques, or new ideas don’t constantly emerge. I still have faith that what is correct will stick, and what is wrong will gradually fall by the wayside. This is how science works, and if Berger does it quicker and more entertainingly than you, then maybe you should speed up, learn how to speak on camera, and ultimately lighten up a little and go watch Cave of Bones again. It’s okay to be excited about this stuff.